- Brain Fog in EDS, POTS and Long COVID: Causes and Practical Ways to Cope - 13 February 2026

- Hypermobility, Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome, and Your Pelvic Floor: A Comprehensive Guide - 13 February 2026

- POTS and Exercise: The First Step Everyone Misses - 27 June 2025

If you live with Ehlers Danlos syndrome (EDS), hypermobility spectrum disorder (HSD), POTS, MCAS, ME/CFS, or long COVID, there is a good chance you already know exactly what people mean when they talk about brain fog (1–4). It is that strange heavy feeling where your thoughts feel padded out, like they are moving through treacle, and things you KNOW seem just out of reach. words slip away mid sentence, concentration vanishes, and even simple decisions can feel oddly overwhelming (2).

People often describe it as though their brain has been wrapped in cotton wool. Not switched off just dulled, slowed and unreliable (2). More frustratingly is how invisible it is to everyone else.

Clinicians and researchers tend to group these experiences under the term “brain fog” (2,5). It is not a diagnosis in itself but a cluster of cognitive symptoms that include poor attention, memory problems, slowed processing speed and mental fatigue (2,5,6). Like trying to recall something you did even 5 minutes ago can sometimes feel impossible. Research now backs up what patients have been saying for years! Brain fog is common across these conditions and has nothing to do with laziness, lack of intelligence or not trying hard enough (2,3,5).

Over time this constant brain fog eats away at our confidence, interferes with education, work and relationships and make people doubt their abilities or feel embarrassed asking for accommodations they genuinely need (3,7). That emotional toll matters just as much as the cognitive symptoms themselves (7,8).

Persistent brain fog can also be a useful signal. It may point toward underlying issues such as autonomic dysfunction, disrupted sleep, chronic inflammation, medication effects or altered blood flow to the brain (2,3,5,6). Many of these factors overlap heavily in EDS related conditions, which helps explain why brain fog shows up so often and why it can fluctuate from day to day (1,3,5).

This article is about making sense of all of that. We will look at what brain fog actually is, why it is so common in EDS and related conditions and what current research suggests is happening under the surface (1–3). From there we will move into practical and evidence based strategies that can help improve day to day thinking, without pretending there is a single magic fix (7,9).

If you have ever felt dismissed, confused or blamed for symptoms you cannot control then this is for you. You are not imagining it and you are certainly not alone (1–3).

This article covers:

ToggleWhat brain fog is, and what it is not

Brain fog is not a formal medical diagnosis (2). It is a patient led term that people use to describe a very real group of cognitive difficulties such as forgetfulness, poor concentration, slowed thinking and a deep sense of mental fatigue (2,5). The term exists because there has not been a better everyday word for the experience, not because the experience itself is vague or unimportant (5).

When researchers actually sit down and listen to patients, the descriptions are very consistent. In studies of people with ME/CFS and related conditions, participants tend to use words like cloudy, blurry, sluggish, and “walking through treacle” to explain what thinking feels like, describing losing thoughts, struggling to focus or blanking out entirely when trying to process information (2,6). These are detailed, embodied experiences of cognitive strain rather than abstract complaints (2,6). Years ago I worked with a client who described it as “opening your mouth and hoping the right sentence falls out” because by the time they finished a thought, the beginning had already slipped away.

Similarly, surveys of teens and young adults with POTS show that brain fog is one of the most common and disruptive symptoms they report (1,3,10). Words like forgetful and cloudy come up again and again, alongside difficulty focusing, thinking, and communicating (1,3). Importantly, these self reported experiences do not exist in isolation. they correlate with poorer performance on objective measures of working memory and information processing speed, showing that this is not just how people feel, but also how their brains are functioning in that moment (3,6).

Brain fog is not the same thing as the normal forgetfulness everyone experiences from time to time. We all lose our keys or forget a name now and then. With brain fog it is more like standing in your own kitchen and not remembering what a cupboard is for or staring at a familiar word until it looks wrong and you are not entirely sure you’ve spelled your own name correctly. Brain fog tends to be more persistent, more intrusive, and far more disruptive to daily life, often fluctuating alongside other symptoms such as fatigue, pain, orthostatic intolerance or allergy symptoms (2,4,5,11).

It is also important to be clear about what brain fog is not. Despite how frightening it can feel, especially when words will not come or concentration suddenly drops, brain fog in conditions like POTS, ME/CFS, and EDS behaves very differently from neurodegenerative dementia (2,6). Cognitive testing usually shows specific difficulties with attention, working memory, and processing speed, but not the progressive, global cognitive decline that characterises dementias (2,6). That distinction matters, both medically and emotionally.

Understanding this difference helps take some of the fear out of the experience. Brain fog can be debilitating, but it behaves very differently from degenerative conditions (2,6). we will start to unpack why these specific cognitive systems are so vulnerable in EDS/HSD conditions, and what that tells us about where brain fog really comes from (1–3,5).

How common is brain fog in these conditions?

One reason brain fog causes so much frustration is how widespread it is across EDS related and overlapping conditions (1,4,11). Once you start looking for it, it shows up in many diagnostic groups.

In people with POTS, brain fog appears to be extremely common. In an online survey of 138 people with physician diagnosed POTS, 96% reported brain fog, and most of them rated it as one of their most difficult symptoms (1). For many, it was not an occasional annoyance; it was a daily limiter (1,3). For one client I spoke with that “limiter” showed up every time she tried to revise for exams. She would read the same paragraph over and over, only to realise she couldn’t remember a single sentence of it five minutes later.

That personal experience lines up with what we see in the lab. Objective testing consistently shows that people with POTS have measurable difficulties with attention, their working memory and processing speed, which become more severe when the brain is under strain, such as during prolonged cognitive tasks (like studying for an exam, or working through something challenging) or when upright for long periods (3,6). In other words, the harder the system has to work, the more the cracks begin to show.

Among people with hypermobile EDS and HSD, formal prevalence figures for brain fog are still emerging, but observational work and patient reported data describe high rates of cognitive complaints, typically alongside fatigue, pain, autonomic symptoms and disrupted sleep (4,11,12). Brain fog rarely appears on its own, it tends to arrive as part of a wider pattern, which makes it easier to dismiss if you are not looking closely (which is a common experience for a lot of people with these conditions) (4,11,12).

For people with ME/CFS, cognitive problems are almost a guarantee. Most patients report them early in the illness and systematic reviews consistently find impairments in attention, memory and information processing, often worsening after physical or cognitive exertion in line with post exertional symptom flares (2,6,13). A common story goes like this: you manage a family event or a work presentation, it feels a good achievement that you got through it and then spend the next two days unable to follow a simple TV plot.

Long COVID has added yet another group to this picture. Across multiple groups, high rates of persistent cognitive dysfunction are reported months or even years after the initial infection with brain fog among the most frequent complaints and often overlapping with dysautonomia, sleep disturbance and also fatigue (4,8,13).

In mast cell disorders, including MCAS, the data are less tidy but still noticeable. Case series and surveys suggest that a large portion of people with MCAS report cognitive difficulties and “brain fog” alongside other mast cell symptoms such as flushing, gastrointestinal problems, and headaches (11,14,15). High quality prevalence figures are still limited, so any exact percentage needs to be taken as tentative rather than definitive. Taken together, this tells us something important. Brain fog is not a niche or rare feature of these conditions, it is a core part of the lived experience for many people (1–4,8,11). The next step is understanding why it keeps appearing across different diagnoses, and what these shared patterns can tell us about what is happening in the brain and nervous system (2,3,5).

Biological mechanisms that can drive brain fog

Brain fog rarely comes from one single source. For most people, it is the result of several systems being under strain at the same time, and which mechanism dominates can change from by the day or even hour, depending on posture, pain, sleep, hormones, illness or cognitive demand (2–4,8). That variability is one reason brain fog can feel so unpredictable and can make many feel helpless.

Autonomic dysfunction and cerebral blood flow

In conditions like POTS, one of the most consistent biological drivers of brain fog is autonomic dysfunction (3,5,6). POTS is defined by an excessive rise in heart rate on standing, but symptoms often include light headed, palpitations, fatigue, and cognitive problems as well (5,16).

When someone with POTS sits upright or stands, blood has a tendency to pool in the lower body rather than returning efficiently to the heart, reducing their effective stroke volume and altering how blood flow is regulated to the brain (5,16). This is why something as ordinary as standing in a hot shower or waiting in a que to buy something can suddenly feel like your brain has gone dimmer, even if you are technically still upright and functioning. Imaging studies using transcranial Doppler show that people with POTS experience larger drops in cerebral blood flow velocity during orthostatic stress than healthy controls, a commonly used proxy for reduced brain blood supply (6).

In a tilt table study of people with ME/CFS and POTS, increasing orthostatic stress led to progressive declines in working memory and information processing, which closely was closely in line with reductions in cerebral blood flow velocity (3). This tells us that as blood flow fell, so did their cognitive performance (3). In another study using a sustained seated cognitive stress test, people with POTS developed significant reductions in cerebral blood flow velocity during a 30 minute task, accompanied by worsening concentration and slowed psychomotor speed, and this was even without standing (6).

Taken together, what this tells us is that these findings help explain why brain fog can appear during everyday activities. You do not have to faint or even feel obviously dizzy for the brain to be operating with reduced oxygen and nutrient delivery. Slower thinking and mental fatigue can emerge quietly in the background (3,6).

Chronic pain and central sensitisation

Chronic pain is extremely common in hEDS, HSD and EDS (4,11,12). Pain is not just a signal. it places a continuous cognitive and emotional load on the brain. Neuroimaging studies across chronic pain conditions show altered connectivity in networks involved in attention and executive function, and people living with persistent pain often perform worse on tasks that require divided attention, working memory or rapid information processing (11,17).

For someone with EDS or HSD, the brain could be spending a significant amount of time and energy monitoring joint position, predicting movement, and modulating pain, leaving fewer resources available for reading, planning, or holding a conversation (4,11,12). I have been told before by clients they can hold a conversation or keep their balance walking across a crowded room, but not both comfortably. Part of their brain is busy silently tracking every step, every joint, every possible misstep. Pain also disrupts sleep, worsens fatigue and increases mood symptoms. Each of those factors can further reduce cognitive efficiency, creating a loop that can be hard to break (11,17).

Sleep disturbance and circadian disruption

Sleep problems are very common in ME/CFS, long COVID, and EDS related conditions: insomnia, poor quality sleep, fragmented nights, and altered sleep timing are all frequently reported (4,8,13,18). Each of these is independently associated with attention and memory problems in both clinical and general populations (8,18).

In long COVID clinics, large portions of patients report new or worsened sleep disturbance, including both insomnia and hypersomnia, which are strongly linked to reduced cognitive and functional capacity (8). Short or disrupted sleep reduces synaptic plasticity (the brain’s ability to strengthen or weaken the communication strength between neurons over time based on activity levels) and interferes with glymphatic clearance, the system responsible for clearing metabolic waste from the brain and even in otherwise healthy people, poor sleep leads to slower reaction times, weaker working memory, and increased experiences of brain fog (8,18).

For those with autonomic dysfunction, night time symptoms such as tachycardia, temperature instability, reflux, or pain can repeatedly interrupt sleep, often leading to noticeably worse cognitive symptoms the following day (4,8,18).

Mast cells, microglia, and neuroinflammation

Mast cells are immune cells found throughout the body this is including around blood vessels and within the meninges (the three protective, fibrous connective tissue membranes, dura mater, arachnoid mater and Pia mater that covers the brain and spinal cord) (11,14,19). When activated, they release mediators such as histamine, cytokines, and proteases, which can influence blood brain barrier permeability and neuronal signalling (11).

Experimental work suggests that mast cell activation can influence microglia, the brain’s resident immune cells, potentially promoting a state of neuroinflammation that alters neuronal function, affects mood and cognitive function (11,19). Theoharides and colleagues have proposed that in conditions such as MCAS and long COVID, chronic mast cell activation combined with microglial priming may contribute to symptoms like brain fog, fatigue, and “chemobrain” although large controlled human studies are still unfortunately limited (11,19).

Clinical cases and observational reports consistently link mast cell related conditions with high rates of cognitive and neuropsychiatric symptoms, including brain fog, anxiety, low mood, and sleep disturbance (14,15,19). It is important to be clear, though, neuroinflammation is a plausible mechanism in some patients, but current evidence does not show that mast cell driven neuroinflammation is the sole or dominant cause of brain fog in everyone with MCAS, EDS or related conditions (14,19).

Post‑viral syndromes including ME/CFS and long COVID

ME/CFS and long COVID share several defining features, including persistent fatigue, post exertional symptom worsening, autonomic dysfunction, and brain fog (2,4,8,13). Neuroimaging reviews in ME/CFS report subtle but consistent changes in brain regions involved in attention and memory, and some studies show markers suggestive of neuroinflammation in subsets of patients (2,13).

In long COVID, high rates of dysautonomia, including POTS and orthostatic intolerance, have been documented, which can contribute to brain fog through the same blood‑flow and autonomic mechanisms already described (4,8). On top of this, sleep disturbance, chronic pain, mood symptoms, and possible mitochondrial dysfunction create a network of stressors, each chipping away at cognitive efficiency (4,8,13).

Metabolic and electrolyte factors

Even mild dehydration can impair attention, executive function have an affect on mood. Experimental studies in healthy adults show that fluid losses of just 1 or 2% of body weight are enough to slow reaction times and increase perceived mental effort (11,20). In POTS a small trial showed that rapidly drinking 500 ml of water improved orthostatic tachycardia and some measures of cognitive performance during upright tilt likely via an acute increase in blood volume and vascular tone (6,21).

Electrolytes such as sodium, potassium and magnesium are essential for generating and transmitting electrical signals in neurons, and both deficiency and excess can impair cognition (11,20). Low sodium or potassium are recognised causes of confusion and cognitive and more subtle, chronic imbalances may contribute to milder but persistent cognitive complaints (20). Magnesium plays a role in energy production and synaptic function, and studies link low magnesium status with poorer memory and higher risk of cognitive impairment though high quality trials in EDS brain fog are limited (11,20).

Hormones and life stages

Hormonal fluctuations across the menstrual cycle, pregnancy, the postpartum period and menopause can influence sleep, temperature regulation, mood and cognition in the general population (18,20). Many individuals with EDS or HSD report worsening orthostatic symptoms and cognitive issues at certain points in their cycle, although rigorous studies in this specific population are still sparse, so these patterns are best seen as common clinical observations rather than firmly quantified effects (4,11,12).

Thyroid hormones are another key factor. Both underactive and overactive thyroids can cause cognitive slowing, poor concentration and memory difficulties through their effects on energy metabolism and brain function (11,20).

Medications and other reversible medical causes

A wide range of medications commonly used in EDS conditions can impair cognition. These include sedating antihistamines, opioids, benzodiazepines, some antidepressants, anticholinergic drugs and muscle relaxants (11,20). There are also many medical contributors to brain fog that are easy to miss such as anaemia, B12 or folate deficiency, uncontrolled diabetes, vitamin D deficiency, untreated sleep apnoea, and thyroid dysfunction (8,11,18,20).

When someone lives with a complex chronic condition, it is tempting for every cognitive symptom to be attributed to EDS or POTS. That shortcut can be costly. Identifying and treating reversible contributors can make a meaningful difference to day‑to‑day functioning (8,11,18).

How EDS and hypermobility increase vulnerability

EDS and hypermobility do not just affect how far joints move. They change the behaviour of connective tissue throughout the body, including ligaments and blood vessels, and often overlap with autonomic dysfunction (4,11,12,16). When vascular connective tissue is stretchier, veins may not push blood back toward the heart as efficiently when you are upright, making blood pooling and orthostatic intolerance more likely (5,16). Over time, that makes it harder to maintain stable circulation to the brain and increases vulnerability to orthostatic intolerance and POTS (5,16).

This fits with what we see clinically. Autonomic symptoms are common in EDS and HSD, with palpitations, dizziness, exercise intolerance, temperature regulation problems, and brain fog showing up again and again (4,11,12,16). Sometimes these symptoms are dramatic, other times they sit in the background, quietly draining energy and mental clarity.

Joint instability adds another cognitive demand. If joints do not give reliable feedback the brain has to stay switched on to keep posture, balance and movement under control and when pain is part of the picture, the load increases further (4,11,12). It is not hard to see how mental fatigue creeps in.

There are also smaller subgroups within hypermobile populations who have conditions such as craniocervical instability or Chiari I malformation, structural changes near the base of the skull that may compress neural structures or alter cerebrospinal fluid dynamics (11,16). Case reports link these issues with headaches, dizziness and cognitive symptoms but population data is limited, and decisions around surgery are complex and highly specialised, so this area needs nuance and expert input rather than blanket assumptions (11,16).

The role of mental health and stress

Living with chronic symptoms that constantly fluctuate is hard. Being dismissed and waiting years for answers and losing parts of your independence or identity all leave a mark (7,9,22). It is therefore, not surprising that anxiety and depression are more common in conditions like POTS and EDS than in healthy controls, and these mood symptoms are associated with worse self reported brain fog and poorer performance on some cognitive tasks (7,9,22). Everyone I’ve worked with experiencing this can remember the exact appointment where they were told “it’s just stress” or “you’re overthinking it” and that memory sits in the back of their mind every time they consider asking for help again.

Trauma also plays a role for many people. PTSD is increasingly recognised in those living with chronic pain and long term medical conditions and is linked to attention being pulled toward threat, reduced working memory capacity, and a sense of constant cognitive overload (17,22). When your nervous system is stuck in protection mode clear thinking becomes much harder (17,22). An observer may see it as “just” filling in a form or replying to an email, but if your body reads it as a potential threat, your attention locks onto every possible danger and there is not much bandwidth left for remembering what you were trying to say.

This does not mean brain fog is “just psychological.” Psychological and biological processes interact and essentially can ping off each other constantly. Stress affects sleep, pain sensitivity, autonomic function, and immune signalling, and physical symptoms, in turn, reinforce anxiety and low mood (8,11,17). Stress itself can activate the autonomic nervous system and mast cells, potentially worsening dysautonomia and inflammatory pathways, so addressing trauma, anxiety, and depression is about reducing one of the many pressures on an already overloaded system, not minimising physical illness (11,14,17,19).

Assessing brain fog: what to discuss with your clinician

A useful assessment starts with patterns, not just labels. When did the brain fog begin? How does it actually feel? Is it a struggle finding words, slowed thinking, memory lapses, or mental exhaustion? What makes it worse, and what makes it ease off? Posture, heat, exertion, pain, poor sleep, stress, or allergy flares can all be relevant (1–3,7).

Certain patterns can be especially informative. Brain fog that ramps up when standing, after hot showers, or in warm environments may point toward orthostatic intolerance or POTS (5,16). Flares linked to food, strong smells, or allergen exposure can suggest a mast cell factor (14,15,19). Fog that closely tracks with insomnia or sleep apnoea symptoms may indicate that sleep assessment should be a priority (8,18).

Blood tests are often part of a sensible work up, not because they explain everything, but because they can catch common and treatable contributors. This usually includes checks for anaemia, iron status, B12, folate, thyroid function, and glucose; vitamin D and other markers may also be considered (8,11,18,20). Fixing something simple can sometimes lift a surprising amount of cognitive fog.

Medication review matters just as much. Sedating antihistamines, opioids, anticholinergic drugs, benzodiazepines, muscle relaxants, and some antidepressants can all impair attention and memory (11,20). Sometimes it is not about stopping a medication entirely, but adjusting timing or dose, or choosing alternatives with fewer cognitive side effects (11,20).

Neuropsychological testing is not always necessary, but it can be helpful when the picture is unclear, when accommodations are needed for work or education, or when there is concern about a progressive neurological condition rather than fluctuating brain fog (7,9,22). There are also situations that need urgent attention such as rapidly worsening cognition, new neurological deficits, seizures, sudden personality change, or severe headaches with neurological signs should never be brushed off and require prompt assessment to rule out serious causes such as stroke, infection, or autoimmune neurological conditions (7,18,20).

The bottom line is simple. Brain fog deserves to be taken seriously and should never been ignored. A careful, curious approach that looks for patterns and reversible contributors can make a real difference to daily life (7–9).

Day‑to‑day strategies: foundations for clearer thinking

There is no single trick that clears brain fog completely. But there are foundations that can make thinking steadier and more predictable over time. None of these are about pushing harder; they are about working with how your system actually behaves (7–9,13).

Energy management and pacing

In ME/CFS and long COVID, pacing is a cornerstone of symptom management, and the same principle is useful for brain fog in EDS, POTS, and MCAS (2,4,8,13). A helpful way to think about this is to imagine that cognitive, physical, and emotional tasks all draw from the same limited energy pot. If you overspend in one area, the cost often shows up later as heavier brain fog, sometimes later the same day or the next (2,7,9).

Some people find it useful to loosely categorise tasks. High load tasks might include complex work, difficult conversations, appointments, or problem solving. Medium load tasks need attention but not deep focus. Low load tasks are simple, familiar, or restorative. The aim is not to label everything perfectly, but to avoid stacking too many high load tasks together (7,9).

Timing matters too. Most people have a window when their thinking is clearest often late morning, but this varies so scheduling demanding tasks into that window can make them more manageable and reduce the spiral of frustration that comes from trying to think clearly when your brain simply is not there (7). Short periods of focused work followed by deliberate breaks can stop subtle overexertion creeping up on you. It is easy to miss the warning signs until brain fog suddenly crashes in later (7,9).

Sleep hygiene and insomnia strategies

Sleep has an outsized influence on cognitive function, and for many people, improving sleep is one of the highest‑return strategies for reducing brain fog (8,13,18). Consistency helps more than perfection: going to bed and waking up at roughly the same time, keeping evenings calmer, and reducing bright light and stimulating screens before bed can all support the brain’s ability to settle (18).

Pain often sabotages sleep, especially in hypermobility. Addressing pain earlier in the evening, using supportive pillows, braces if advised, and adjusting bedding to reduce joint strain can make a real difference (4,11,12). For persistent insomnia, cognitive behavioural therapy for insomnia (CBT‑I) has strong evidence and can be adapted for people with chronic illness, focusing on rebuilding trust between your brain and sleep rather than forcing rest (18).

If there are signs of sleep apnoea such as loud snoring, pauses in breathing, waking up gasping, or feeling completely unrefreshed despite enough time in bed a sleep study matters. Treating apnoea can dramatically improve daytime thinking for some people (18,20).

Movement and physical conditioning adapted for EDS and POTS

Movement supports brain fog in several ways. It helps blood flow, supports autonomic regulation, and over time can reduce pain, but with EDS and POTS it has to be approached carefully (4,5,16). Many POTS protocols start with recumbent or semi recumbent exercise. Things like recumbent cycling, rowing, or supine leg and core work, build muscle pump function without triggering orthostatic symptoms too early (5,16,23).

Movement does not have to be formal exercise. Short, gentle bouts spread through the day calf raises, light marching, or brief stretches, can reduce pooling during long periods of sitting and may slightly sharpen cognitive clarity for some people (5,7). Because joint instability is part of the picture in hEDS and HSD, working with a physiotherapist who understands hypermobility can be invaluable, with the goal of stability and control rather than maximum range (4,11,12,23).

Progress needs to be slow and deliberate. Delayed symptom flares are common. Keeping a simple activity and symptom diary can help you spot whether increases are helping or quietly costing you later, especially if you experience post‑exertional symptom worsening (2,13,23).

Environment and sensory load

The brain fog puzzle is not just internal. Environment matters more than people often realise. Busy, noisy, bright, or hot environments increase cognitive load and autonomic activation, and for someone already vulnerable that can tip thinking over the edge quickly (5,7,16).

Many people rely on practical tools here: noise cancelling headphones, sunglasses or hats and cooling devices. These are not indulgences, they are ways of reducing unnecessary strain in shops, classrooms, offices, or public transport (5,7). Heat deserves special mention. Warm environments dilate blood vessels and can worsen orthostatic symptoms. Staying cool using fans, drinking cold fluids, and avoiding long hot showers can reduce both physical symptoms and brain fog (5,16).

Visual clutter also adds load. Simplifying a workspace, closing unnecessary tabs, and reducing visual noise can make it easier to stay oriented and follow tasks through, even tidying up a little in the area you are spending time in (7,9).

Cognitive strategies

When brain fog is bad, trying to hold everything in your head is exhausting. Externalising memory and planning can free up a surprising amount of mental energy. Simple systems work best: to do lists, phone reminders, calendars, whiteboards, sticky notes (7,9,22). The goal is reliability, not perfection. One or two tools used consistently beat five systems used occasionally.

Breaking tasks down helps too. Large, vague tasks demand a lot of executive function. Smaller, concrete steps are easier to start and easier to finish, and progress feels more tangible, which matters when motivation is fragile (7,9). Single‑tasking is usually more efficient than multitasking when attention is limited, and grouping similar tasks together can reduce the mental cost of switching gears (7,22).

When word‑finding becomes difficult, slowing down helps. Describing the idea, using gestures, or talking around the word can keep communication flowing until it catches up. Most people are more patient than we fear, especially when they understand what is happening (7,22).

Self‑compassion and coping with guilt

Brain fog does not just affect thinking; it hits identity. Many people who struggle with it were previously high functioning, driven, or perfectionists. When thinking slows, frustration, shame, and self criticism often rush in to fill the gap (7,9,22).

Self compassion is not about giving up. It is about recognising that brain fog is real, common in chronic illness, and not a personal failure (7,9,22). Reducing self attack lowers stress, and that alone can free up some cognitive bandwidth (17,22). Being open with trusted people can help too. Friends, family, colleagues, teachers, or employers cannot accommodate what they do not understand; clear communication reduces misunderstandings and makes support more likely (7,9).

Psychological approaches such as acceptance and commitment therapy or compassion focused therapy can be especially helpful. They do not aim to eliminate symptoms; they help people build meaningful lives alongside uncertainty and cognitive variability (9,17,22). None of these strategies are about fixing you. They are about giving your brain the conditions it needs to do its best on any given day.

Targeting specific contributors

Once the foundations are in place, it can be helpful to look at specific drivers of brain fog and address them directly. Not everything here will apply to everyone, and nothing is about doing all of it. This is about having options and choosing the ones that fit your body and circumstances (5,7,9).

Managing POTS‑related brain fog

For many people with POTS, brain fog tracks closely with how well orthostatic symptoms are controlled (1,3,5,6). One simple but sometimes effective tool is hydration, particularly using what is known as a water bolus. A small controlled study showed that drinking around 500 ml of water quickly reduced orthostatic tachycardia and improved some cognitive measures during tilt testing, probably via stimulation of receptors in the gut and portal circulation that increase vascular tone (6,21).

In the day to day life, some people find that taking water before prolonged standing, such as showering or going shopping, can take the edge off symptoms, although this is not universal and needs to be adapted to individual tolerance, especially if there are heart or kidney conditions in the background (5,16). Salt and electrolytes can also play a role. Increasing sodium intake, under medical guidance, can expand plasma volume and improve orthostatic tolerance in many people with POTS, and electrolyte solutions or oral rehydration salts can help maintain both fluid and sodium levels especially in hot weather or during illness (5,16,23). Very high salt intake is not appropriate for everyone and should be supervised.

Compression is another practical lever. Garments that include the abdomen and thighs, not just the calves, are more effective at reducing orthostatic symptoms (5,16). Physical counter manoeuvres can help too, leg crossing, tensing the legs and glutes, calf raises, or marching in place can temporarily increase venous return and sometimes rescue short term drops in cognitive clarity (5,16).

Exercise training can improve POTS symptoms for some people, particularly when it starts with recumbent aerobic work and gentle resistance training (16,23). Brain fog outcomes are less well studied, and for those with overlap with ME/CFS or post exertional symptoms, exercise needs to be individualised and monitored carefully; pushing through often backfires (2,13,23). Medications are sometimes part of the picture. Drugs such as fludrocortisone, beta blockers, midodrine, ivabradine, and other meds are used to influence heart rate, blood volume, or vascular tone. Some people notice improvements in brain fog when orthostatic symptoms are better controlled, but these medications can have side effects and interactions, so decisions are best made with a clinician who understands dysautonomia rather than by trial and error alone (5,16,23).

Addressing MCAS‑related contributors

When mast cell activation is part of the mix, reducing mediator release can sometimes improve cognitive symptoms (11,14,15,19). Histamine is a major player here. Non sedating H1 antihistamines, such as cetirizine or loratadine, along with H2 blockers like famotidine, are commonly used in MCAS. Observational reports suggest that combined H1 and H2 blockade can improve both physical symptoms and brain fog in some people, although high quality trials focused specifically on cognition are limited and requires more research (14,15).

Sedating first generation antihistamines are a different story. Drugs like diphenhydramine can worsen attention and memory and are generally avoided for daytime use when brain fog is already a problem (11,20). Mast cell stabilisers are sometimes used as well. Cromolyn sodium is prescribed in some cases, and while evidence is largely from small studies, some people report clearer thinking when mast cell activity is better controlled (14,15,19).

Supplements like quercetin and luteolin are often discussed online. They have mast cell stabilising and anti inflammatory properties in preclinical studies, and small uncontrolled human studies suggest possible benefit for neuroinflammatory symptoms, but evidence remains limited and they can interact with medications or be inappropriate for some people (11,19). These are conversations to have with a knowledgeable clinician, not decisions to make based on anecdotes alone.

Diet can matter too. Some people notice that reducing high histamine or histamine liberating foods helps reduce flares, including brain fog, although responses vary widely (14,15). Food lists can be a starting point, but strict long term restriction without guidance risks nutritional problems. A dietitian familiar with MCAS can help strike a safer balance (14,15).

Managing sleep problems

Sleep deserves its own attention because of how strongly it shapes cognition (8,13,18). In long COVID clinics, insomnia, hypersomnia, and mixed sleep patterns are common, and similar issues show up in EDS, HSD, and ME/CFS populations (4,8,13,18). Non drug approaches such as CBT‑I, stimulus control, sleep restriction therapy, relaxation techniques, and circadian rhythm support have good evidence for improving sleep quality and daytime functioning (18).

When there is suspicion of conditions like restless legs syndrome, periodic limb movements, or parasomnias, sleep studies can clarify what is going on and guide targeted treatment. Improving sleep architecture can reduce brain fog simply by restoring more restorative rest (18,20). Sleep medications need regular review. Sedative hypnotics and some antidepressants or antipsychotics can worsen cognition, especially with long term use, so the balance between helping sleep and blunting thinking needs ongoing attention (18,20).

Supporting mental health

Mental health care is not an optional extra when it comes to brain fog (7,9,22). Psychological therapies adapted for chronic illness including CBT, ACT, trauma focused therapies, and mindfulness based approaches can reduce distress and cognitive load; when worry, rumination, and hypervigilance ease, attention and memory often improve as a downstream effect (9,17,22).

In POTS, research shows that anxiety and depression are associated with poorer performance in areas like attention and short term memory (9,22). Addressing mood does not mean symptoms were imagined; it means removing another drain on an already stretched system. When medications such as SSRIs or SNRIs are considered, potential benefits for mood and sometimes autonomic symptoms need to be weighed against side effects like sedation, agitation, or sleep disruption, and these trade offs look different for each person (9,20,22).

Nutrition, electrolytes, and micronutrients

Adequate nutrition underpins everything. Highly restrictive diets, especially when self directed, can quietly worsen fatigue and cognition through calorie or micronutrient deficits (11,20). Clinicians often check iron status, B12, folate, and vitamin D when brain fog is prominent, because deficiencies in any of these can contribute to cognitive complaints, even when levels are only mildly low (11,20).

Omega‑3 fatty acids have been linked with modest improvements in mood and attention in some studies, although evidence specific to EDS or POTS related brain fog is limited (11,20). Magnesium may help individuals who are deficient or borderline, but routine high‑dose supplementation without evidence of low status is not well supported (11,20).

Experimental and emerging ideas, with caution

There are also approaches being discussed that sit firmly in the experimental space. These are worth knowing about, but not adopting uncritically.

Some flavonoids, particularly luteolin, have been proposed as treatments for brain fog in long COVID, MCAS, and chemotherapy related cognitive impairment. The interest comes from animal studies and small human series suggesting anti inflammatory and mast cell stabilising effects (11,19). At present, evidence is preliminary, dosing is unclear, and long‑term safety data are limited. These should be seen as experimental adjuncts, not established treatments (11,19).

Ketogenic and very low carbohydrate diets have also been explored. A recent review suggested that nutritional ketosis might help neurological symptoms in long COVID by providing an alternative brain fuel and reducing inflammation, but signals of benefit are early and based on small studies (24). These diets are restrictive and can carry risks, particularly for people with gastrointestinal issues, metabolic conditions, or eating disorder histories, so they should only be undertaken with medical and dietetic support (24).

Oxygen based therapies have been tried by some clinicians in POTS and long COVID, based on evidence that cerebral blood flow can drop substantially during orthostatic stress (6,8). Increasing inspired oxygen can raise arterial oxygen content, but controlled studies looking specifically at brain fog outcomes are scarce, and long term use also comes with cost and potential risks (6,8). At present, this remains an experimental approach that should only be considered under specialist supervision.

The common thread here is caution. New ideas are worth exploring, but the goal is always to do less harm, not more (11,19,24).

Working, studying, and parenting with brain fog

Brain fog does not stay neatly contained. It spills into the parts of life that rely most on thinking clearly and staying regulated. Reading takes longer. Writing feels harder than it should. Meetings blur together. Conversations derail halfway through a sentence. Time slips. Emotional bandwidth shrinks. When your role involves work, study, or caring for other people, that cognitive drag can be exhausting and, at times, deeply demoralising (7,9,22).

One important thing to know is that support is not a favour. In many countries, legal frameworks allow for reasonable adjustments for people living with chronic health conditions, and documentation from a clinician, and sometimes a neuropsychologist, can support requests for accommodations without you having to over explain or justify yourself repeatedly (7,9,22). In practice, what helps is often quite simple: recorded lectures or meetings so information can be replayed, written instructions rather than relying solely on verbal ones, task lists that live outside your head, reduced pressure to multitask, quiet workspaces, and flexibility around working remotely on days when symptoms flare (7,9,22). None of these lower standards, they lower unnecessary friction.

For students, extra time in exams, rest breaks, or alternative assessment formats can be the difference between demonstrating understanding and being limited by processing speed (7,13). These adjustments exist for a reason.

Parenting with brain fog brings its own challenges. Children need consistency, attention, and emotional availability, and that can feel painfully hard when your thinking is slow or fragmented. Many parents find that simplifying routines helps shared calendars, batch cooking on better days, and fewer moving parts during the week (7,9). Being honest, in an age appropriate way, often helps too. Saying something like “my brain feels tired today” gives children a framework that does not involve blame or fear and helps them understand why a parent might be quieter, slower, or need more rest, without feeling pushed away (7,22).

None of this makes you a worse worker, student, or parent. It makes you someone adapting intelligently to a fluctuating nervous system (7,9,22).

Putting it together: building a personalised plan

Brain fog rarely responds to a one size fits all approach because it rarely comes from one place (2–4,7). The most effective approach is usually to step back and ask which contributors are doing the most damage right now, not in general, but right now.

For one person, brain fog may spike with standing, heat, and dehydration. In that case, prioritising POTS management, hydration strategies, compression, and cooling can bring the biggest gains (5,6,16,21,23). For someone else, the fog may be driven mainly by insomnia, trauma, or ongoing stress, making sleep support and psychological care the most sensible starting points (8,9,17,18,22).

These priorities can shift over time. What matters is staying responsive rather than rigid (7,9). Many people benefit from working with an interdisciplinary team, not because it is fancy but because it is practical: a clinician familiar with EDS, POTS, or MCAS, a physiotherapist who understands hypermobility, a psychologist who works with chronic illness and, where needed, a dietitian or occupational therapist (4,5,11,12,15,16,23). When these pieces talk to each other, the plan becomes coherent instead of overwhelming.

Tracking symptoms can help more than people expect. A simple journal or app noting brain fog severity, triggers, posture, sleep, medications, and interventions can reveal patterns that are hard to see day to day (7,9). Over time, this makes it easier to drop what does not help, avoid what makes things worse, and keep what genuinely improves clarity (7,9).

The goal is not perfect cognition. It is predictability: enough mental clarity, often enough, to live the life that matters to you (7,9,22). Brain fog may be part of your story, but it does not get to be the whole narrative.

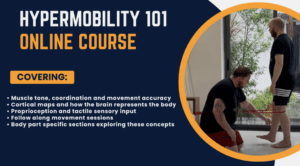

Enjoying Our Resources? Why Stop Here?

If you’ve found value in our posts, imagine what you’ll gain from a structured, science backed course designed just for you. Hypermobility 101is your ultimate starting point for building strength, stability, and confidence in your body.

References:

- Ross, A.J., Medow, M.S., Rowe, P.C. and Stewart, J.M. (2013) ‘What is brain fog? An evaluation of the symptom in postural tachycardia syndrome’, Clinical Autonomic Research, 23(6), pp. 305–311.

- Ocon, A.J. (2013) ‘Caught in the thickness of brain fog: exploring the cognitive symptoms of chronic fatigue syndrome’, Frontiers in Physiology, 4, 102.

- Ocon, A.J., Messer, Z., Medow, M.S. and Stewart, J.M. (2012) ‘Increasing orthostatic stress impairs neurocognitive functioning in chronic fatigue syndrome with postural tachycardia syndrome’, Clinical Science, 122(5), pp. 227–238.

- NICE (2021) Myalgic encephalomyelitis (or encephalopathy)/chronic fatigue syndrome: diagnosis and management. Guideline NG206. London: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence.

- Raj, S.R. et al. (2020) ‘Canadian Cardiovascular Society position statement on postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome (POTS) and related disorders of orthostatic intolerance’, Canadian Journal of Cardiology, 36(3), pp. 357–372.

- Arnold, A.C. et al. (2020) ‘Cerebral blood flow and cognitive performance in postural tachycardia syndrome: insights from sustained cognitive stress test’, Journal of the American Heart Association, 9(11), e017861.

- Anderson, J.W. et al. (2014) ‘Cognitive function, health-related quality of life, and symptoms of depression and anxiety sensitivity are impaired in patients with the postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome (POTS)’, Frontiers in Physiology, 5, 230.

- Dani, M. et al. (2021) ‘Autonomic dysfunction in “long COVID”: rationale, physiology and management strategies’, Clinical Medicine, 21(1), pp. e63–e67.

- Adolescent fatigue, POTS, and recovery: a guide for clinicians (2014) Journal of Adolescent Health, 54(3), pp. 272–277.

- Dysautonomia International (2013) What is brain fog? An evaluation of the symptom in postural tachycardia syndrome (patient information PDF). Available at: http://www.dysautonomiainternational.org/pdf/BrainFog.pdf (Accessed 10 February 2026).

- Theoharides, T.C. (2015) ‘Brain “fog,” inflammation and obesity: key aspects of neuropsychiatric disorders improved by luteolin’, Frontiers in Neuroscience, 9, 225.

- Hakim, A.J. and Grahame, R. (2003) ‘A simple questionnaire to detect hypermobility: an adjunct to the assessment of patients with diffuse musculoskeletal pain’, International Journal of Clinical Practice, 57(3), pp. 163–166.

- Myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome: cognitive impairment review(background) in NICE NG206 evidence tables (2021).

- Weinstock, L.B., Brook, J.B., Myers, T.L. and Goodman, B. (2023) ‘Mast cell activation syndrome: a primer for the gastroenterologist with specific focus on neuropsychiatric manifestations’, Digestive Diseases and Sciences, 68(3), pp. 813–832.

- Castells, M. (2024) ‘Mast cell activation syndrome: current understanding’, Allergy, Asthma & Clinical Immunology, 20, 52.

- Low, P.A., Sandroni, P., Joyner, M. and Shen, W.K. (2009) ‘Postural tachycardia syndrome (POTS)’, Journal of Cardiovascular Electrophysiology, 20(3), pp. 352–358.

- Hruska, B., Cullen, P.K. and Delahanty, D.L. (2025) ‘Brain fog and cognitive dysfunction in posttraumatic stress disorder: an evidence-based review’, Journal of Traumatic Stress, 38(1), pp. 1–18.

- Berry, R.B. et al. (2017) The AASM manual for the scoring of sleep and associated events: rules, terminology and technical specifications. Version 2.4. Darien, IL: American Academy of Sleep Medicine.

- Theoharides, T.C., Cholevas, C., Polyzoidis, K. and Politis, A. (2021) ‘Long-COVID syndrome-associated brain fog and chemofog: luteolin to the rescue’, BioFactors, 47(2), pp. 232–241.

- Benton, D. (2011) ‘Dehydration influences mood and cognition: a plausible hypothesis?’ Nutrients, 3(5), pp. 555–573.

- Jordan, J. et al. (2000) ‘Water potentiates the pressor effect of ephedrine in autonomic failure’, Hypertension, 35(1), pp. 383–389.

- Kavi, L. et al. (2016) ‘Postural tachycardia syndrome: multiple symptoms, but easily missed’, British Journal of General Practice, 66(651), pp. 274–276.

- Shibata, S. et al. (2012) ‘Short-term exercise training improves the cardiovascular response to exercise in POTS’, Journal of Physiology, 590(15), pp. 3495–3505.

- Saudi Journal of Medical and Pharmaceutical Sciences (2025) ‘The role of nutritional ketosis in managing neurological symptoms in long COVID patients: a systematic review’, Saudi Journal of Medical and Pharmaceutical Sciences, 11(4), pp. 210–224.