- POTS and Salt: What the Science Actually Says - 18 February 2026

- Why the Beighton Score Matters More Than It Should - 18 February 2026

- Brain Fog in EDS, POTS and Long COVID: Causes and Practical Ways to Cope - 13 February 2026

If you’ve spent any time in the hypermobility world, you’ve probably heard the same question more than once.

“What’s your Beighton score?”

It’s become almost a badge. A number that seems to decide whether your symptoms are valid, whether you qualify for further investigation, orx whether you’re sent home with a polite smile and a “you’re fine.”

On paper, the Beighton score is simple. It’s a 9-point joint flexibility screen designed to assess generalised joint laxity (1). It’s quick. It’s easy to perform. And when used correctly, it’s reasonably reliable. That’s exactly why it’s been adopted so widely in clinics across the world.

But somewhere along the way, this simple screening tool started carrying far more weight than it was ever designed to.

In many settings, it now acts as a gatekeeper for hypermobility diagnoses, including hypermobile Ehlers-Danlos syndrome and Hypermobility Spectrum Disorder (1). And that’s where things start to go wrong.

Because when the Beighton score is treated as the test for hypermobility, rather than a small piece of a much bigger puzzle, people fall through the cracks.

Spend five minutes in any patient forum and you’ll see it. People being told, “Your Beighton is 2, so you can’t have EDS.” Others scoring 9 out of 9 and being sent away with, “There’s nothing wrong with you.” Both scenarios leave patients confused, frustrated, and often doubting their own experience (2)(3). The problem is they could very well be hypermobile and not flexible due to the nervous system trying to protect the joints.

Here’s the uncomfortable truth. The Beighton score was never designed to diagnose EDS (1)(4). It was created as a screening tool for joint laxity, not as a standalone diagnostic instrument for complex connective tissue disorders. Yet in real world clinical practice, it’s still frequently used as if it holds that power (1)(4).

That mismatch between intention and application is what creates the chaos.

A low score does not automatically mean you are not hypermobile in meaningful ways., A high score does not automatically explain pain, instability, fatigue, dysautonomia, or any of the systemic issues that so often accompany hypermobility disorders. The number alone cannot tell your whole story.

And this is where we need to tread carefully.

I’m not here to throw the Beighton score under the bus. It has value. It gives clinicians a standardised, repeatable way to assess certain joints. In research settings especially, that consistency matters. But it must be understood for what it is: a narrow lens looking at a very wide landscape.

Modern, ethical clinical practice does not stop at a number. It asks deeper questions. It looks at injury history, instability patterns, systemic features, family background, and how your body actually behaves in daily life. It respects the Beighton score, but it doesn’t worship it.

This article isn’t about dismissing the Beighton score. It’s about putting it back in its rightful place.

We’re going to break down how it’s measured, what your score really means, why it helps, and where it fails. Most importantly, we’ll look at what good assessment should actually look like when hypermobility spectrum disorders are on the table.

Because you deserve more than a number.

Hypermobility 101: From Bendy Joints to Hypermobility Spectrum

Before we get any further into the Beighton score, there is a need to zoom out for a moment.

Because this is where the lines of things are often muddled.

Joints that move beyond that which is considered typical or normal for the general population is called hypermobility. That, in itself is a physical characteristic. There are plenty of people who are naturally flexible. Some never have one problem because of it.

But also, hypermobility can be part of a diagnosis.

When joint laxity becomes symptomatic, when it becomes unstable, painful, repeatedly injured, is associated with systemic features within the body or limits function, then it stops being an interesting party-trick and starts being clinically significant. That’s where terms such as Generalised Joint Hypermobility (GJH), Hypermobility Spectrum Disorder (HSD) and hypermobile Ehlers-Danlos syndrome (hEDS) come in. (1) (4)

So the main difference isn’t whether or not hypermobility “is” or “isn’t” a diagnosis.

It’s this:

Joint hypermobility in itself is a trait.

Clinically significant hyper mobility is a diagnosis.

And that difference matters.

If we don’t provide a clear separation of those two things, then we’re in danger of reducing complicated, systemic conditions down from how far somebody’s elbows turn.

Now let’s go and break down this properly

This article covers:

ToggleLocalised vs Generalised Joint Hypermobility

When we talk about hypermobility, we’re simply describing joints that move further than expected.

But not all hypermobility looks the same.

Localised joint hypermobility means increased range in one joint or a small cluster of joints. Maybe it’s just your elbows that hyperextend. Maybe it’s your ankles that roll easily. Everything else feels fairly stable.

That’s localised.

Generalised joint hypermobility (GJH) refers to increased passive range across multiple limbs and often the axial skeleton as well. That includes areas like the spine, ribs, and pelvis. It’s a more global pattern of connective tissue laxity rather than one isolated joint being extra flexible (1)(5).

And this is where context becomes everything.

Hypermobility can be:

Completely asymptomatic

Helpful in certain environments like dance, gymnastics, or circus arts

Or a marker of an underlying systemic connective tissue disorder

That last category includes Hypermobility Spectrum Disorders, hypermobile Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, other EDS types, Marfan syndrome, and Loeys-Dietz syndrome (1)(4).

Notice the wording carefully.

Hypermobility is a feature of these conditions. It is not automatically the condition itself.

You can have Generalised Joint Hypermobility and live your whole life without chronic pain or instability. Equally, you can have significant functional problems with only modest visible laxity.

And this is where relying too heavily on a single joint screen becomes problematic.

From “Benign” Hypermobility to HSD and hEDS

Historically, the terminology did patients no favours.

For years, people who were clearly bendy and clearly in pain were labelled with “benign joint hypermobility syndrome.” The word benign implied harmless. Anyone living with recurrent subluxations, chronic pain, fatigue, dysautonomia, or gastrointestinal dysfunction would strongly disagree.

In 2017, the International Classification of the Ehlers-Danlos syndromes aimed to clarify things (4).

Two major categories were defined:

Hypermobile EDS (hEDS) with stricter diagnostic criteria

Hypermobility Spectrum Disorders (HSD) for individuals with clinically significant hypermobility who do not meet full hEDS criteria but still experience real and impactful symptoms (4)

This was an important shift.

It acknowledged that hypermobility can sit on a spectrum of severity. You don’t need to meet every criterion for hEDS to have a legitimate disorder. If hypermobility is driving instability, pain, and dysfunction, that matters.

And here is the concept that often gets lost in clinic rooms.

Diagnosis is never based on the Beighton score alone.

Under the 2017 framework, assessment requires a whole clinical picture. That includes:

- Joint hypermobility

- Systemic connective tissue features

- Family history

- Chronic musculoskeletal complications

- Exclusion of alternative diagnoses (4)(1)

The Beighton score contributes to identifying generalised joint hypermobility. But it is one component within a much broader structure.

Hypermobility disorders are diagnosed based on patterns, history, systemic involvement, and clinical reasoning.

Not just how far your thumbs move.

And once we understand that properly, the Beighton score starts to look very different.

Now we can finally examine it for what it actually is.

What the Beighton Score Is (and Is Not)

Now that we’ve set the literally groundwork around what exactly hypermobility is, we’ve got to do some proper bearding in another direction, we’ve got to look properly at the Beighton score itself. Because for something in such wide use, that’s often not well understood.

The Beighton score is a laxity joint measurement. It is not a diagnosis. It is not a severity scale. It is not a pain index. It does not inform you how unstable your joints feel at the end of a long day though. It does not determine the number of times that your shoulder slip out this year. It is just a measure of passive range in a limited number of specific movements.

That distinction matters.

If it is used correctly, the Beighton score is a useful, standardised method of identifying generalised joint hypermobility. When not understood it turns it into a blunt tool that simplifies complex bodies.

Let’s break down what it is all about.

The 9-Point Test, Step by Step

The Beighton score is composed of five manoeuvres with a maximum score of 9 points.

First is passive little finger to go past 90 degrees extension. There are 2 possible points, 1 point for each side.

Second, the passive apposition of the thumbs to the forearm. Again, one point for each side.

Third, hyper extension of the elbow past 10 degrees. One point per elbow.

Fourth, knee hyper extension (beyond 10 degrees). One point per knee.

Finally, Forward Trunk Flexion where the person bends forward with the legs in the straight position and hands palm flat on the floor. That movement has a point (6)(7).

Add them up and you have some score between 0 and 9.

On paper, it’s simple. And it’s one of its strengths. It’s quick. It’s reproducible. It does not require complex equipment. But how it’s performed is important.

Ideally, the person should be warm and not be forced into pain. We’re not testing the ability to transcend discomfort. We’re measuring laxity passivity. Elbows and knee should be measured with a goniometer, but in the real world, many times using the eye, clinicians make an educated estimate. That creates the variability.

Each movement- Should be clearly yes or no. There should not be “almost” points. Ambiguity decreases the reliability and comparability between examiners.(8)(9)

The Beighton score is best used if it is applied with care and consistency.

Cut-Offs and Age Adjustments

Patients exhibiting Generalised Joint Hypermobility under the 2017 hEDS diagnostic criteria have age-adjusted cutoff values (4).

Children and adolescents pre-pubertally require 6 or more score. Adults up to 50 years old need 5 or more. Adults over 50 require 4 or more.

This adjustment reflects something that is simple but important: connective tissue stiffens with separating aging. A score that may have been 7 at 15 years of age may not be a 7 at 45 years. Injuries accumulate. Hormones shift. Bodies change.

Here’s where subtlety comes into play.

If somebody scores one less, then the criteria are open to historical features. That could mean being able to put palms flat on the floor in childhood, to be able to do the splits easily, recurrent dislocations or being described as “double jointed” growing up (4).

So if a 35-year-old scores 4 instead of 5 that does not necessarily rule out Generalised Joint Hypermobility. Context matters. History matters.

Unfortunately, that nuance is lost in some cases in practise.

What It Actually Measures

The Beighton score quantifies the passive laxity of 5 specific movement patterns, in that clinic, on the day of assessment.

That’s it.

It does not measure pain. It does not measure for frequency of subluxations/dislocations. It does not assess fatigue, dysautonomia, gastrointestinal dysfunction, skin fragility, pelvic organ problems and the overall systemic features that commonly accompany hypermobility disorders(1)(4).

It does not measure strength. It is not evaluating the motor control. It does not quantify proprioception.

In other words, it does not measure how your body apparently works in real life.

It measures joint range.

Such information is valuable. But it is only one layer of the whole picture. When we consider that, then the Beighton score ends up being a handy tool. When we forget it, it becomes something it was never converted into.

And that’s where the power struggle begins.

Strengths of the Beighton Score

Before we tear it apart we need to be fair.

There is a reason this Beighton score has withstood the test of time. It didn’t embed in research, guidelines and clinical practise by chance. But when used appropriately, it has certain things it does very well.

High Reliability and Practicality

One of the greatest aspects about the Beighton score is that it is reliable. When the clinicians follow standardised instructions, different examiners tend to give similar scores. That inter-rater reliability is usually stated as being substantial to excellent (8)(10). In other words, I assume that if two trained clinicians properly assess the same person, they are likely to come to the same number.

Intra-rater reliability is also high. Individual clinicians often tend to report the same scores when they re-assess the same patient over time assuming that the range of movement in the joint has not truly changed.(8)(10) That consistency is valuable, especially in a research setting.

It also is extremely practical. The test takes only a few minutes. It takes little if any equipment. A goniometer is too good for knees and elbows but many settings operate without one. The manoeuvres are easy to teach, easy to reproduce and straightforward to document (8)(7).

From a systems point of view, that is important. Quick and repeatable tools are attractive in busy clinics. In large population studies, simplicity is a must. The Beighton score provides a win for both fronts.

Shared Language in Research and Guidelines

Another major strength is that Beighton score is providing a shared language.

It is embedded in epidemiological studies which look at the prevalence of Generalised Joint Hypermobility. It is present in all aspects of research in sports medicine attempting to examine the risk of injuries with respect to ACL tears, the risk in ankle instability, and pathology of the hip. This is included in the diagnostic criteria for hEDS (2017) and is a component of GP toolkits and specialist guidelines (1)(4)(11).

Because of that, when one person, a clinician, says “Beighton 6 out of 9” there is immediate understanding by other professionals what is being discussed. It results in a common reference point between disciplines and between countries.

Now, that is not to say that it is a perfect measure of Generalised Joint Hypermobility. Even its most proponents know that it has limits in that respect (1)(12). But as regards research and policy, standardisation is valuable. Without a common metric it is almost impossible to compare.

So we have to give credit where credit’s due. The Beighton score has good reliability. It is practical. And it provides clinicians and researchers something in which they can all work.

But reliability is different to validity.

And that’s where things start to begin unravelling.

Limitations: Where the Beighton Score Breaks Down

The Beighton score works well as a quick screen for certain joints. The problem is what happens when we expect it to represent something much broader.

Because once we move beyond what it was designed to do, the cracks become obvious.

Joint Selection and Regional Blind Spots

The Beighton score only tests five patterns of movement. Pinkies. Thumbs. Elbows. Knees. Forward trunk flexion.

That’s it.

It does not assess shoulders. It does not check ankles and midfeet. It does not test in any meaningful way hips. It does not evaluate the cervical spine, ribs, sacroiliac joints or the temporomandibular joints1 (7).

And yet, ask most hypermobile patients where their worst instability live. Shoulders are common. Ankles are common. Hips are common. SI joints and ribs are common.

There is a clear lack of congruency between what the Beighton score is measuring and where people are often struggling.

Research reflects this. The Beighton scores are not a good correlation with more detailed shoulder laxity measures. A high Beighton score is not suggestive of shoulder laxity and a low Beighton score is certainly not suggestive of a lack of shoulder laxity (13). That should give us pause.

Work looking at foot and ankle dysfunction in hypermobile kids has shown there is significant impairment that the Beighton score alone will miss out of (14). So the technicality is that a child can “pass” below threshold and still show meaningful instability of the lower limb.

When a screening tool considers none of the joints traditionally affected in a large portion of the population on which it is being used, there are bound to be blind spots.

It Doesn’t Map Cleanly onto “True” GJH

Here is where we have to distinguish between reliability and validity.

Beighton score is reliable. But whether it is an accurate representation of true generalised joint hypermobility is less clear.

Systematic reviews have consistently demonstrated that reliability is good, but validity as a comprehensive indicator of Generalised Joint Hypermobility is questionable (1)(5)(12). Part of the problem is a methodological one. There are differences in cut-off levels used in different studies. Some use 3 or more. Others use 4,5 and 6. That inconsistency makes comparisons messy and even interpretation messier.

There is also no universally accepted gold standard for how Generalised Joint Hypermobility should be defined. In some validity studies the Beighton score is effectively compared against composite measures that already have components of Beighton. That runs the risk of circular reasoning (1)(12).

In some populations such as chronic fatigue, the research has suggested that the categorisation of Beighton scores or dividing into low, medium and high may be more meaningful than a simple yes or no threshold15. That makes intuitive sense. Humans are never black and white in their biology.

The difficulty is this: we are often applying this kind of blunt numerical cut-off to defining something that is likely to occur on a spectrum.

Age, Sex and Ethnicity: Baked-In Biases

Joint mobility decreases with age. That is normal physiology.

Newer meta analyses indicate that possibly higher cut offs may be more appropriate for younger adults and lower cut offs for older adults in order to reflect natural stiffening of connective tissue over time16.(12) The new criteria for 2017 take account of this by changing the thresholds for different age groups (4).

Yet in practice, a lot of clinics will actually use it as a flat “4 or more equal’s hypermobile” at all ages. That risks the patients falling into the trap of false negatives for older individuals whose laxity has decreased with time but whose history seems to be clearly supportive of Generalised Joint Hypermobility (1)(4).

Sex differences also exist. Women tend to show more mobility at surface level than men. Certain ethnic groups, naturally, have higher or lower average range of motion (16)(12). A single global cut-off does not take these differences into account, and may inadvertently lead to an over-diagnosis of some groups and an under-diagnosis of others.14, 12

The more specific tool does not adjust for these demographic variables. Clinicians have to perform that context manually. When they do not, bias creeps in.

No Grading of Severity, Symptoms or Function

Finally, the Beighton score is binary on the level of the joint. Each movement is scored 0 or 1. There is no difference between slightly hyperextending an elbow, and dramatically hyperextending it (1).

There is also no consideration of the way that laxity behaves in actual life.

The score does not take into consideration frequency of subluxations or dislocations. It does not take account of activity limitation. It is not accounting for pain behaviour, tiredness and autonomic symptoms, or fear of movement.(1)(4)

This is why it is possible to have a 9 out of 9 Beighton score and still be relatively well functioning, while another with a 1 out of 9 score is severely limited and disabled (1)(4).

The number does not tell you how the system behaves under a load.

And once you see that clearly, it really becomes obvious why the use of the Beighton score as a gate-keeper, rather than as one component of a more comprehensive assessment, generates so many problems.

Next, we need to take a look at what good clinical practise actually looks like, when we go beyond the number.

Real-World Consequences: How Over-Reliance on Beighton Helps and Harms

Up until now we were rather technical. Reliability. Validity. Cut-offs. Joint selection.

But all that doesn’t matter actually if we don’t talk about what’s going on in clinic rooms.

Because when the Beighton score is being used as it is meant to be used, it helps. Where it’s over-relied upon, it hurts. And that harm is not a hypothesis. It plays out in very real ways.

Gatekeeping and Missed Diagnoses

One of the problems most commonly seen is under-diagnosis.

Take older adults. Joint mobility is reduced with ageing. Surgeries happen. Injuries accumulate. Scar tissue builds. A person who might have scored 7 out of 9 at 15 years old might score 3 or 4 at 50. In this situation, if[he or she]were to look only at the current number without regard to history, the door to more could be closed prematurely(1)(4)(17).

Yet many of these individuals report a history of childhood extreme flexibility, repeated dislocations, chronic pain and systemic features consistent with HSD or hEDS. The laxity was there. It’s just not as full as it used to be, as it is no longer fully visible.

Athletes have a similar picture. Years of strength training, joint protection measures or even surgery can limit the passive range. On paper, the Beighton score is not very impressive. In reality, there may be a long standing history of instability, soft tissue injury and persistent pain (18)(11).

When we reduce the conversation to number we risk not seeing the pattern.

This is not some issue talked about only in academic circles. Patient communities often share storeys of having a low Beighton score to close down any further checking altogether. “You can’t have EDS, you just scored a 2 on it.” End of discussion (2)(3)(19).

That type of gatekeeping doesn’t simply postpone diagnosis. It erodes trust.

And once you lose trust it’s hard to get back.

Over-Diagnosis and Confusion

The opposite is also a problem.

A high score on the Beighton scale is sometimes used as shorthand for “you must have EDS.” But a high score is not sufficient to meet the criteria for a diagnosis.

Hypermobile EDS requires systemic features, patterns of family history, and exclusion of the possibility of other heritable connective tissue disorders such as Marfan syndrome or Loeys-Dietz syndrome, and other potential causes of hypermobility (1)(4).

Without that bigger picture evaluation, we stand a chance of treating benign hyperlaxity as a genetic connective tissue disorder.

In the field of sports medicine, in particular, a high Beighton score may simply indicate constitutional flexibility. That still may have some implications in terms of injury risk and how you plan to rehabilitate yourself, but it’s not necessarily pathological automatically (18)(11).

Over-diagnosis causes problems of its own. It can make a lot of unnecessary fears. It can result in people thinking their body is broken beyond repair. And, sometimes it distracts other treatable contributors to symptoms.

Both extremes, under-recognition and over-labelling, arise because of the same problem, that of trying to make the Beighton score out to be more than what it actually is.

Psychological Impact and Trust Issues

This is the part we don’t discuss enough.

Patients with low Beighton scores but obvious instability, pain, and systemic symptoms are often accused of being dismissed by their physicians or of exaggerating. If life experience is invalidated through a number, it feels like gaslighting even if that was never the intention of the clinician (20)(21)(2)(3).

On the other side, very high scoring patients may get told, sometimes bluntly ‘Well, you have EDS. There’s nothing we can do.” That message can be one of fear, avoidance and inevitability rather than constructive management (20).

Neither approach is helpful.

The overall effect, particularly in the chronic pain and complex symptoms population, is distrust that is developing between patients and providers. When people feel they are being unheard, they go elsewhere for the answers. That can result in misinformation, interventions where not necessary or increased anxiety.

All of this from a nine point joint screen.

The Beighton score is not the bad guy. It’s the over-reliance on it that is causing the problem.

So the true question then becomes what does good clinical practise look like when we go beyond the number?

That’s where we are headed next.

Alternative and Complementary Tools

If the Beighton score isn’t enough on its own, the next logical question is this: what do we use in conjunction with it then?

The solution is not to throw it out. The answer is to either widen the lens.

Good assessment of hypermobility is multifactorial. It combines physical testing, treating histories and system screening. Let’s examine some of the tools used in filling the gaps.

The 5-Part Questionnaire (5PQ)

The 5-Part Questionnaire is one of the most useful – and simplest – additions to a Beighton-based assessment.

Instead of testing current range of movement, asks instead about historic, lifetime history. The questions are about whether you have ever been able to put your palms flat on the floor, bend your thumb to your forearm or done splits or childhood contortion-type movements, had recurrent shoulder or kneecap dislocations, or considered yourself “double-jointed” (22)(17).

It’s short. It’s practical. And importantly, it records something that is often overlooked in the Beighton score – what your body was before age, surgery or stiffness or guarding alters the picture.

In many populations, two or more ‘yes’ answers are suggestive of generalised hypermobility of joints(22) That makes it especially useful for older people or athletes who have stiffened over time but obviously had significant laxity when they were younger.

It is also extremely useful in telehealth settings or situations in which physical examination is limited (22). If it were not possible to physically measure joint angles, a structured historical screen is much better than guesswork.

The 5PQ is not a replacement for physical examination. But it strengthens the story.

Expanded Joint Scores and Regional Tools

Several expanded scoring systems evaluate a greater number of joints and use a graded scale, as opposed to a binary yes or no scoring system. Tools such as the Hospital del Mar criteria, the Bulbena score or the Rotes-Querol score try to capture a broader picture of the hypermobility (9)(23).

These tools include extra joints and sometimes severity gradings (to provide sometimes more nuance than a 0 or 1 per movement).

In the case of children specific assessment tools are of particular relevance like e.g. the Lower Limb Assessment Score (LLAS). Hypermobile children commonly have foot and ankle dysfunction and the Beighton score alone may not reveal important lower limb problems (14).

The downside to this is practicality. These assessments take a longer time. They are not as widely validated as the Beighton score. And many clinicians are simply not familiar with them.5(12)

So while it may have theoretical advantages, it is inconsistent to see their adoption in everyday practice.

Self-Report and Emerging Technologies

Research is also being carried out to see if the assessment of hypermobility can be brought into the twenty-first century.

Self-reported Beighton scoring based on line drawings has been shown to be in good agreement with clinician scoring in population studies24. That is not a perfect, although it is promising, because when they do huge studies like in epidemiology.

Even more interesting are computer-vision and pose-tracking systems being developed in order to automate Beighton cheque in suspected populations with EDS (25). The concept here is that digital imaging together with motion tracking may be an objective way to quantify joint range as opposed to just using examiner judgement.

These technologies are exciting, especially for the telemedicine use and for research. But at the moment they are still experimental.

Technology may have a way to perfect measurement. It is not going to replace clinical reasoning.

Best Practice: Multi-Tool, Multi-System Assessment

This is the part that really matters.

Good clinics do not use the Beighton score in isolation. They combine tools (4).

A thorough assessment typically includes:

A Beighton score

A historical screen such as the 5PQ

Joint-specific examination of problematic regions such as shoulders, hips, ankles, and spine

A systemic symptom review, including skin, vascular, gastrointestinal, autonomic, and pelvic floor features

A detailed family history

Careful exclusion of alternative diagnoses

When you layer these elements together, patterns emerge.

And that is the core message here.

No single score can define hypermobility spectrum disorders or hypermobile Ehlers-Danlos syndrome. Not the Beighton score. Not the 5PQ. Not any expanded scale.

It is the pattern that matters (1)(12)(4).

Once clinicians shift from chasing numbers to identifying patterns, assessment becomes more accurate, more ethical, and far more patient-centred.

And that is what modern hypermobility care should look like.

Myths, Misconceptions and FAQs

When a tool becomes widely used, it also becomes widely misunderstood.

The Beighton score has picked up a lot of mythology over the years. Some of it comes from oversimplified teaching. Some from rushed appointments. Some from internet echo chambers. And some from well-meaning clinicians trying to create clarity where the science is still evolving.

Let’s clear a few things up properly.

Myth 1: “The Beighton score is the gold standard for hypermobility”

Reality: It’s widely used and it’s got good reliability. But that by no means automatically makes it a gold standard.

Systematic reviews have repeatedly demonstrated that although reliability is very good, its validity as a definitive measure of Generalised Joint Hypermobility is questionable (1)(5)(12). There does not follow a unanimously accepted gold standard for defining GJH.

In other words, the Beighton score is a useful tool. It is not a final and conclusive rule when determining whether someone is hypermobile in a clinically significant way.

Myth 2: “You can’t have hEDS or HSD if your Beighton score is low”

Reality: This is one of the most harmful of all the misunderstandings.

The diagnostic guidelines of 2017 explicitly allow for a diagnosis when the Beighton score is just below the cut-off when the individual has strong historical evidence and systemic features (4). That nuance is actually written right into the criteria.

Older adults lose visible mobility with time. People who have had stabilising surgery may not demonstrate large passive ranges anymore. Athletes may have stiffened through years of strengthening. Yet their history may include childhood extreme flexibility, recurrent dislocations and long standing instability (1)(17).

Community reports have often been made of situations where a low Beighton score has been used to end further investigation altogether (2)(3). That is not consistent with the published criteria.

The presence of a low current score does not repair a hypermobile history.

Myth 3: “If my Beighton score is 9, I definitely have EDS”

Reality: The high the Beighton score, the more flexible you are with manner of movements tried. It does not automatically mean that you have a connective tissue disorder.

Diagnosis of hypermobile EDS should be based on a wider pattern. That includes systemic features, family history, chronic complications related to the musculoskeletal system and exclusion of other conditions such as Marfan syndrome or Loeys-Dietz syndrome(1)(4).

Some people score 9 out of 9 and have no pain, no instability and no systemic symptoms. That can be benign hyperlaxity, rather than some sort of pathology.

Flexibility is not in and of itself is a diagnosis.

Myth 4: “If my joints are stiff now, it means I was never hypermobile”

Reality: Bodies change.

Joint mobility decreases during ageing. Injuries alter movement. Surgery limits range. Chronic guarding & pain may limit motion Strength training can increase the stiffness of the tissues over time (16).

This is precisely why we have such helpful tools as the 5 Part Questionnaire. Childhood Flexibility & Dislocations from Early Age historical ability to perform splits or palms to floor movements is clinically relevant (22) (17).

Your current range of motion may not be a good measure of your lifetime positioning behaviour of your connective tissue.

Myth 5: “Beighton scores are the same everywhere”

Reality: Context matters.

Age influences mobility. Sex influences average range of joint. Ethnicity determines the range of flexibility at the baseline level. Examiner technique has an effect on scoring consistency (16)(12)(8).

A flat global cut is, without any context, at risk of either over identifying some populations, or under identifying others. The number in itself is not interpretable solely because of demographic and clinical context.

Beighton score are not free from bias. It requires well thought interpretation.

Myth 6: “If it hurts to do the test, I must not be hypermobile”

Reality: Pain may restrict the degree to which you are willing or able to move.

If the joint is inflamed, unstable, or injured recently, you may not be able to go to your actual passive end-range. That does not necessarily mean that laxity is negligible. It may simply be an expression of protective guarding or nociceptive limitation (15)(2).

The Beighton score reflects what you are sharing at the moment. And pain can conceal underlying mobility.

And this is perhaps the key takeaway from this whole section.

Beighton score is a picture in the moment. Not a biography.

When we do a biography of it we get confused. When we can take it as a snapshot as part of a much bigger clinical storey it will be useful.

And that’s where we’re going next.

Practical Guidance: How to Use Your Beighton Score in Real Life

At this point, we’ve taken the science apart. We’ve looked at strengths, we have looked at limitations and we have looked at consequences in the real world.

Now let’s bring it back to something that is simple.

Basically, what do you do about your Beighton score?

For Patients

First, remember the following: your Beighton score is one data point. It is not your identity. It is not a judgment of the reality of your symptoms. It is not an indication of just how “bad” your body is.

It’s a screen.

If you’re going for an appointment, and particularly if you’re going for an appointment where hypermobility or EDS is going to be considered, please go in prepared. Similar to most people, write down your childhood flexibility. Were you able to do the splits? Palms flat to the floor? Was it possible to bend your thumb to your forearm? Would you have been labelled double-jointed?

Document injuries. Recurrent dislocations. Unpleasant surprises for the athlete and their teammates, such as: “Sprains that shouldn’t have happened”; Surgeries. Long-standing instability.

If you have photos or videos of previous years, they can be remarkably helpful. They cover objective historical background.

Also list non-joint symptoms. Gastrointestinal issues. POTS-like symptoms. Skin fragility. Easy bruising. Pelvic organ prolapse. Hernias. Wound healing problems. These systemic features are important as part of the criteria in 2017 (4).

If you are dismissed by a clinician just because of a Beighton score, avoid flustering, and steer your voice and conversation in another direction. You might ask:

“Is it possible to consider the hEDS or HSD 2017 criteria along with each other?”

My score is just below the cut-off. Could we take my childhood history and the 5-part questionnaire as the criteria propose?” (4)(17)

Would there be anything that I can do about my shoulders, my ankles or hips because that’s my main problem area?”

You’re not rebelling against the fundamentals of authority. You’re fighting for a full assessment;

And that’s reasonable.

For Clinicians and Therapists

If you are a clinician reading this, the Beighton score absolutely has a place.

Use it for documentation of baseline laxity of joints. Use it to compare across time. Use it in order to communicate effectively with other professionals.

It is a common language. That has value.

But one should not use it to rule out unilaterally Hypermobility Spectrum Disorder, Hypermobile EDS or other connective tissue conditions when history and systemic features strongly suggest them to be the case (1)(4)(12).

When scales are marginally or low but you still suspect a lot then broaden the lens. Use the 5 Part Questionnaire. Examine joints not covered in Beighton score. Take a detailed family, ask for family history. Review systemic features. Referral to a clinician acquainted with the 2017 criteria and other related disorders should be considered if needed (22)(4).

The Beighton score should be used to support clinical reasoning. It should not replace it.

A Realistic, Ethical Role for the Beighton Score

The Beighton score is not an enemy.

It is a useful, reliable screening tool. It deserves a place in the clinical toolbox (8)(1). The issue starts when it is used as a blunt gatekeeper of yes or no in terms of complex diagnoses and access to care (1)(12)(4).

Hypermobility Spectrum Disorders as well as Hypermobile EDS is a multi-system condition. They need to do pattern recognition, to interpret context, and to consider the other causes and result in thoughtful exclusion.

The future of assessment will probably go beyond a mere 9 point flexibility screen. Age and population-sensitive cut-offs will improve. Historical questionnaires and expanded joint examinations will still be used to compliment physical testing. Advances in genetics, imaging, and perhaps biochemical markers will hopefully lead to the day when we are no longer stuck relying on surface-level range of motion as our primary arbiter as to who is “hypermobile enough.”16(12)(26)

Until the time comes, the answer is not to throw the Beighton score out.

It is to use it responsibly.

Because the point is not to run around playing with numbers.

The point is to learn patterns, minimise harm, and provide patients with assessment that is accurate, ethical, and reality-based, in regard to the full reality of how their bodies work.

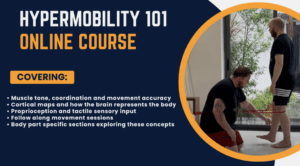

Enjoying Our Resources? Why Stop Here?

If you’ve found value in our posts, imagine what you’ll gain from a structured, science backed course designed just for you. Hypermobility 101is your ultimate starting point for building strength, stability, and confidence in your body.

References:

- Malek, S., Reinhold, E.J. and Pearce, G.S. (2021) ‘The Beighton Score as a measure of generalised joint hypermobility’, Rheumatology International, 41(10), pp. 1707–1716. doi: 10.1007/s00296-021-04832-4.

- Reddit user discussion (2024) ‘is beighton scoring system actually accurate to diagnose someone with hypermobility?’, r/Hypermobility. Available at: https://www.reddit.com/r/Hypermobility/comments/1g6wq7c/is_beighton_scoring_system_actually_accurate_to/ (Accessed: 16 February 2026).

- Reddit user discussion (2025) ‘Low beighton score barrier to diagnosis?’, r/ehlersdanlos. Available at: https://www.reddit.com/r/ehlersdanlos/comments/1j9yegs/low_beighton_score_barrier_to_diagnosis/ (Accessed: 16 February 2026).

- Malfait, F., Francomano, C., Byers, P., Belmont, J., Berglund, B., Black, J., Bloom, L., Bowen, J.M., Brady, A.F., Burrows, N.P., Castori, M., Cohen, H., Colombi, M., Demirdas, S., De Backer, J., De Paepe, A., Fournel-Gigleux, S., Frank, M., Ghali, N., Giunta, C., Grahame, R., Hakim, A., Jeunemaitre, X., Johnson, D., Juul-Kristensen, B., Kapferer-Seebacher, I., Kazkaz, H., Kosho, T., Lavallee, M.E., Levy, H., Mendoza-Londono, R., Pepin, M., Pope, F.M., Reinstein, E., Robert, L., Rohrbach, M., Sanders, L., Sobey, G.J., Van Damme, T., Vandersteen, A., van Mourik, C., Voermans, N., Wheeldon, N., Zschocke, J. and Tinkle, B. (2017) ‘The 2017 international classification of the Ehlers–Danlos syndromes’, American Journal of Medical Genetics Part C: Seminars in Medical Genetics, 175(1), pp. 8–26. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.c.31552.

- Juul-Kristensen, B., Schmedling, K., Rombaut, L., Lund, H. and Engelbert, R.H.H. (2017) ‘Measurement properties of clinical assessment methods for classifying generalized joint hypermobility—A systematic review’, American Journal of Medical Genetics Part C: Seminars in Medical Genetics, 175(1), pp. 116–147. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.c.31540.

- Beighton, P., Solomon, L. and Soskolne, C.L. (1973) ‘Articular mobility in an African population’, Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases, 32(5), pp. 413–418. doi: 10.1136/ard.32.5.413.

- Cleveland Clinic (2022) ‘Beighton Score’, Cleveland Clinic Health Library. Available at: https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/diagnostics/24169-beighton-score (Accessed: 16 February 2026).

- Bockhorn, L.N., Vera, A.M., Dong, D., Delgado, D.A., Varner, K.E. and Harris, J.D. (2021) ‘Interrater and intrarater reliability of the Beighton score: a systematic review’, Orthopaedic Journal of Sports Medicine, 9(1), p. 2325967120968099. doi: 10.1177/2325967120968099.

- Juul-Kristensen, B., Østengaard, L., Hansen, S., Boyle, E., Junge, T. and Hestbaek, L. (2017) ‘Inter-examiner reproducibility of tests and criteria used to identify generalised joint hypermobility in children’, BMC Pediatrics, 17, p. 178. doi: 10.1186/s12887-017-0928-0.

- Boyle, K.L., Witt, P. and Riegger-Krugh, C. (2003) ‘Intrarater and interrater reliability of the Beighton and Horan Joint Mobility Index’, Journal of Athletic Training, 38(4), pp. 281–285.

- Lower rates of return to sport in patients with generalised joint hypermobility two years after ACL reconstruction: a prospective cohort study (2023) BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders, 24, p. 619. doi: 10.1186/s12891-023-06747-4.

- Alexander, M. (2023) ‘A systematised review of the Beighton Score compared with other commonly used measurement tools for assessment and identification of generalised joint hypermobility (GJH)’, Journal of Clinical Rheumatology Research, 4(1), pp. 1–23.

- Whitehead, N.A., Kim, T., Ma, C.B. and Li, X. (2018) ‘Does the Beighton Score correlate with specific measures of shoulder joint laxity?’, Orthopaedic Journal of Sports Medicine, 6(4), p. 2325967118768848. doi: 10.1177/2325967118768848.

- Ferrari, J., Parslow, C., Lim, E. and Hayward, A. (2005) ‘Joint hypermobility: The use of a new assessment tool to measure lower limb hypermobility’, Clinical and Experimental Rheumatology, 23(3), pp. 413–420.

- Juul-Kristensen, B., Schmedling, K., Rombaut, L., Lund, H. and Engelbert, R.H.H. (2017) ‘Measurement properties of clinical assessment methods for classifying generalized joint hypermobility—A systematic review’, American Journal of Medical Genetics Part C: Seminars in Medical Genetics, 175(1), pp. 116–147. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.c.31540.

- Stuive, I., Bossema, E.R., Middendorp, H., Schoones, J.W., Busch, M.A., Middelkoop, M. and Beelen, A. (2021) ‘Assessment of systemic joint laxity in the clinical context: Relevance and replicability of the Beighton score in chronic fatigue’, Clinical Rheumatology, 41(3), pp. 867–877. doi: 10.1007/s10067-021-05936-4.

- Engelbert, R.H.H., Juul-Kristensen, B., Pacey, V., de Wandele, I., Smeenk, S., Woinarosky, N., Sabo, S., Scheper, M.C., Russek, L. and Simmonds, J.V. (2025) ‘Generalized joint hypermobility in adults: A systematic review with meta-analysis to identify data driven cut-offs using the Beighton score’, Arthritis Care & Research. doi: 10.1002/acr.70017.

- Special Needs Jungle (2017) ‘What’s in a name: Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome types get an important makeover’, Special Needs Jungle, 17 March. Available at: https://www.specialneedsjungle.com/ehlers-danlos-syndrome-types-important-makeover/ (Accessed: 16 February 2026).

- Cureus case study (2024) ‘A comprehensive case study of a hyperlaxity dilemma: An injury-prone young athlete’, Cureus, 16(2), p. e54755. doi: 10.7759/cureus.54755.

- Facebook discussion (2025) ‘Beighton test not accurate for hypermobility assessment’, Hypermobility Support Group. Available at: https://www.facebook.com/groups/1045061640575808/ (Accessed: 16 February 2026).

- The EDS Clinic (2024) ‘Is Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome a scam?’, The EDS Clinic, 23 July. Available at: https://www.eds.clinic/articles/ehlers-danlos-syndrome-scam (Accessed: 16 February 2026).

- Giving a Name to Awareness (2025) ‘The truth about EDS: A doctor’s experience with medical dismissal with Linda Bluestein’, GNA Now Podcast, 21 August. Available at: https://gnanow.org/podcast/the-truth-about-eds-a-doctor-s-experience-with-medical-dismissal-with-linda-bluestein.html (Accessed: 16 February 2026).

- Glans, M., Humble, M.B., Elwin, M. and Bejerot, S. (2020) ‘Self-rated joint hypermobility: the five-part questionnaire evaluated in a Swedish non-clinical adult population’, BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders, 21, p. 174. doi: 10.1186/s12891-020-3067-1.

- Juul-Kristensen, B., Østengaard, L., Hansen, S., Boyle, E., Junge, T. and Hestbaek, L. (2018) ‘Inter- and intra-rater reliability for measurement of range of motion in joints included in three hypermobility assessment methods’, Musculoskeletal Science and Practice, 37, pp. 103–111. doi: 10.1016/j.msksp.2018.07.003.

- Romeo, D.M., Lucibello, S., Musto, E., Brogna, C., Ferrantini, G., Velli, C., Cota, F. and Ricci, D. (2018) ‘Development and validation of self-reported line drawings of the modified Beighton score for the assessment of generalised joint hypermobility’, BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders, 19, p. 19. doi: 10.1186/s12891-018-1932-x.

- BioMedical Engineering OnLine (2026) ‘Development and evaluation of a vision pose-tracking based Beighton score tool for generalized joint hypermobility in individuals with suspected Ehlers-Danlos syndromes’, BioMedical Engineering OnLine, 25, p. 3. doi: 10.1186/s12938-026-01527-4.

- Wiley Online Library (2024) ‘Bridging the diagnostic gap for hypermobile Ehlers-Danlos syndrome’, American Journal of Medical Genetics Part A. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.63857.