- Brain Fog in EDS, POTS and Long COVID: Causes and Practical Ways to Cope - 13 February 2026

- Hypermobility, Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome, and Your Pelvic Floor: A Comprehensive Guide - 13 February 2026

- POTS and Exercise: The First Step Everyone Misses - 27 June 2025

If you’ve ever been described as or told you are “double jointed” unusually bendy or hypermobile this article is written with you in mind. For a long time, hypermobility has been treated as a party trick or at best a joint issue that only really matters, if something dislocates. What often gets missed is how far reaching connective tissue actually is, and how deeply it influences parts of the body we rarely talk about. One of the most overlooked areas is the pelvic floor.

The connection between hypermobility, Ehlers Danlos syndrome, and pelvic floor dysfunction is still flying under the radar in healthcare and is why so many conditions can be mistaken for it. I see this play out again and again. People live for years sometimes decades dealing with urinary leakage, persistent pelvic pain, constipation, or pain during sex. They’re passed between specialists, given fragmented explanations, or told everything looks “normal” so nothing should be wrong. What rarely gets discussed is that the underlying issue may not be the bladder, bowel or pelvis itself but the quality of the connective tissue holding everything together.

This guide pulls together the best available evidence to explain why people with hypermobile joints are more likely to struggle with pelvic floor problems. We’ll look at how and why these issues develop, how to recognise them in yourself or your patients, and what can actually be done to move things in the right direction. It’s Important to remember that this conversation isn’t just for women. Pelvic floor dysfunction affects people of all genders, and hypermobility does not discriminate.

I’ve written this for those living in these bodies, but also for clinicians, trainers, and therapists who work with them and want a clearer framework that actually makes sense. Nothing here is based on guesswork or trends. Every scientific point is grounded in published research, with references provided as we go, so, you can follow the evidence for yourself and understand where it comes from.

This article covers:

ToggleUnderstanding Hypermobility and Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome

What is hypermobility?

When I ask people about their history, often I have noticed a pattern, they remember being a very “bendy kid” who could drop in to the splits or turn their elbows out to entertain their friends or as a party trick. However, no one ever framed it to them as anything more than a party trick. Fast forward a couple decades and that same person is now living with widespread pain, fatigue, gut issues or pelvic symptoms that all seem really unconnected, that is, until you realise they’re all running on the same connective tissue blueprint.

Joint hypermobility simply means that a joint moves beyond what is considered a typical or sometimes safe range for someone’s age, sex and background. In everyday terms people often hear words like “double jointed” or “very bendy” used to describe it. On its own, hypermobility is not automatically a problem. Many children are naturally flexible and stiffen up as they get older, and hypermobility is more common in women and in people of Asian and African descent (1). In some settings hypermobility can even be advantageous. Activities like dance, gymnastics, and yoga often reward flexibility, which may be why these populations have a higher density of hypermobility among them.

Things start to look different when that extra movement comes with pain repeated injuries, fatigue symptoms that seem to involve far more than just the joints. In those situations, hypermobility may be part of a hypermobility spectrum disorder or one of the Ehlers Danlos syndromes. This is where the conversation shifts from flexibility as a trait to connective tissue as a system wide issue.

What are hypermobility spectrum disorders?

Hypermobility spectrum disorders, often shortened to HSD, were formally defined in the 2017 International Classification (1). The aim was to describe people who have symptomatic joint hypermobility but do not meet the full diagnostic criteria for hypermobile Ehlers Danlos syndrome. It’s Important to note, HSD is not a lesser or watered down diagnosis. Research shows that people with HSD can experience pain, fatigue, and functional limitation that is just as severe as those diagnosed with hEDS (2).

The word “spectrum” matters here. Symptoms vary widely both in how they show up and how much they affect the day to day life. HSD is even further divided into subtypes based on how hypermobility presents (1):

- Generalised HSD, where hypermobility is widespread and accompanied by musculoskeletal symptoms.

- Peripheral HSD, where hypermobility is mainly seen in the hands and feet.

- Localised HSD, affecting a single joint or a specific group of joints.

- Historical HSD, where someone was clearly hypermobile earlier in life but has lost flexibility over time due to age, injury, or surgery.

Clinically, these distinctions help describe presentation, but they do not reliably predict how much support someone may need.

What is Ehlers-Danlos syndrome?

The Ehlers Danlos syndromes are a group of inherited connective tissue disorders that primarily affect collagen (1). Collagen is the most abundant protein in the body and provides structure and strength to skin, ligaments, tendons, blood vessels, and internal organs. When collagen is produced incorrectly or has altered structure, the effects are rarely limited to one area. Instead, multiple body systems can be involved.

The 2017 International Classification recognises 13 subtypes of Ehlers-Danlos syndrome (1). Each subtype is defined by a particular pattern of clinical features and, where known, specific genetic mutations. The most commonly encountered forms include hypermobile EDS, classical EDS, and vascular EDS. Of these, hypermobile EDS is by far the most common.

Hypermobile EDS is estimated to affect somewhere between 1 in 500 and 1 in 5,000 people, depending on how strictly the criteria are applied (1)(3). Unlike other subtypes, there is currently no known genetic marker for hEDS (1). Diagnosis is therefore entirely clinical, which adds another layer of complexity and uncertainty for many patients.

Diagnosing hypermobility: the Beighton score and 2017 hEDS criteria

The Beighton Score is a nine point screening tool used to assess generalised joint hypermobility (1). It looks at five simple movements, scored on both sides where relevant:

- Bending the little finger back beyond 90 degrees.

- Touching the thumb to the forearm.

- Hyperextending the elbow beyond 10 degrees.

- Hyperextending the knee beyond 10 degrees.

- Placing the palms flat on the floor with straight knees.

The cut off for generalised joint hypermobility depends on age and sex (1). The threshold is higher for children, slightly lower for adults and lower again for those over 50. If someone scores just below the cut off, a history of clear hypermobility earlier in life can still satisfy the requirement.

For hypermobile EDS, meeting the Beighton threshold is only the first step. The full 2017 diagnostic criteria require generalised joint hypermobility, additional systemic features or musculoskeletal complications, and the exclusion of other connective tissue or autoimmune conditions (1). These criteria have been criticised for being overly strict with concerns that many highly symptomatic people are left without a formal hEDS diagnosis. Those individuals are typically classified under HSD, and in practice management and support should be very similar.

The trifecta: hEDS, POTS, and MCAS

I once had a client, Sarah who would describe her mornings like this: “If I stay sitting I’m mostly fine, the second I stand up to shower, my heart goes crazy like I’m running a marathon, I suddenly need to pee really badly and I feel light headed. On paper she had a “normal” heart, bladder and “probably IBS or anxiety” in reality she had POTS, mast cell issues and a pelvic floor on high alert. all layered on top of connective tissue that couldn’t provide the usual support.

A pattern that shows up repeatedly in clinics is the overlap between hypermobile EDS or HSD, postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome, and mast cell activation syndrome. This cluster is informally referred to as the “trifecta” Studies suggest that a significant proportion of people with POTS also meet criteria for hypermobility and that autonomic and mast cell related symptoms are commonly reported in those with EDS (4).

This overlap matters. These conditions do not exist in isolation, and each can amplify the others, bouncing off each other to make each worse than it would be alone. When we start talking about pelvic floor dysfunction later in this guide, this interconnectedness becomes particularly relevant, as autonomic regulation, connective tissue integrity and pain processing all play a role.

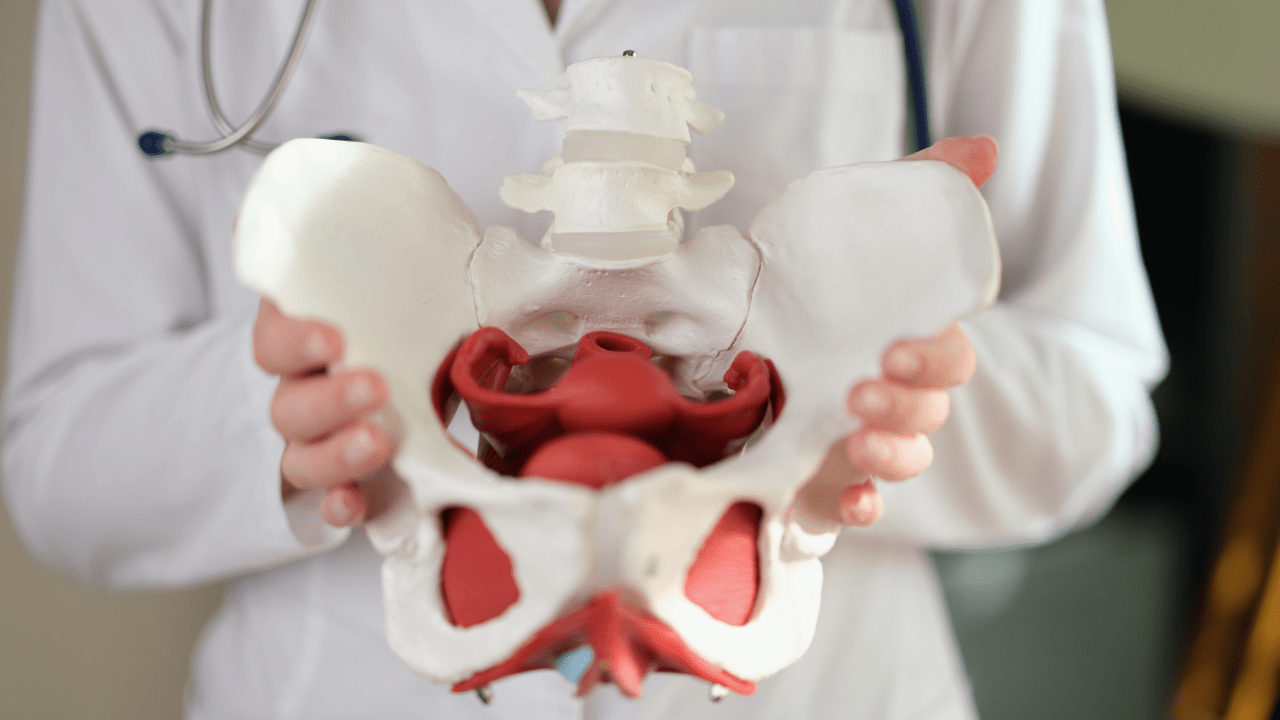

The Pelvic Floor, Anatomy and Function

What Is the Pelvic Floor?

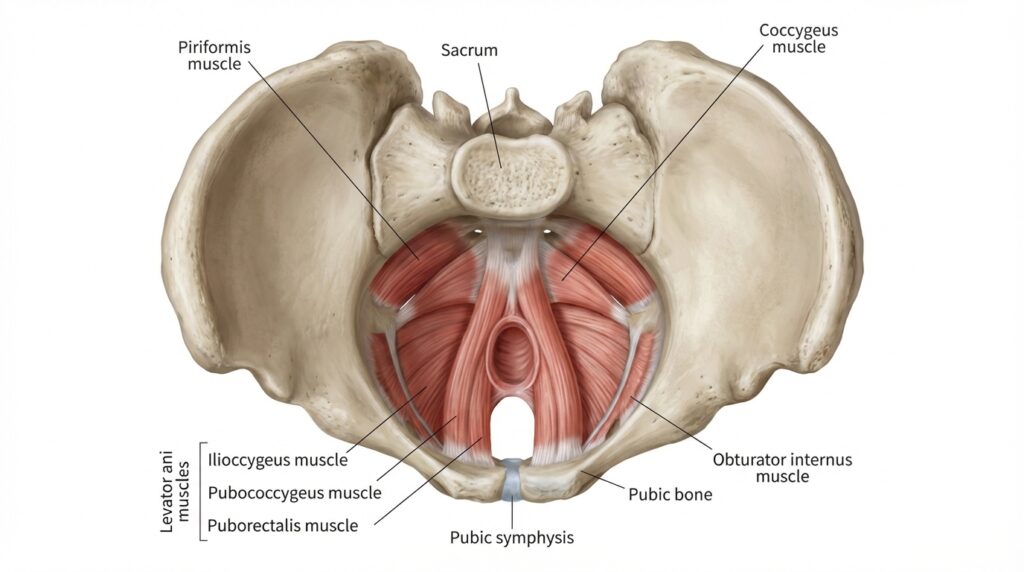

The pelvic floor is often talked about in vague terms, yet, it is one of the most important and complex structures in the body. Put simply it is like a hammock, a system of muscles, ligaments, connective tissue and nerves that sits at the base of the pelvis. It runs from the pubic bone at the front to the tailbone at the back, and from one sit bone to the other, forming a supportive foundation underneath the pelvic organs.

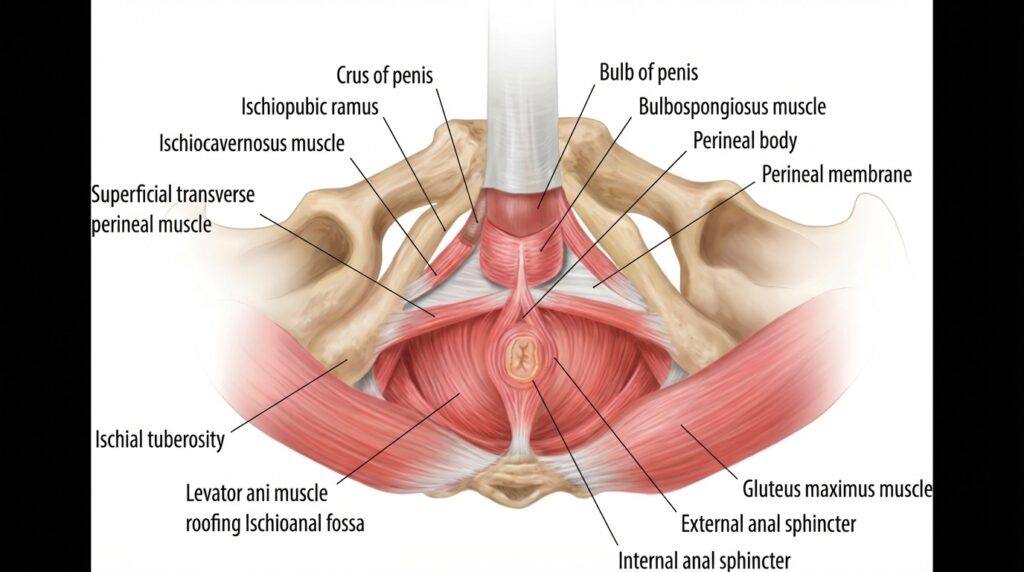

Rather than being a single muscle, the pelvic floor is organised into layers that work together. Closest to the surface are the superficial muscles, including the bulbospongiosus, ischiocavernosus, perineal muscles, and the external anal sphincter. These muscles are heavily involved in sexual function, sensation and sphincter control.

Deeper is the main support system formed by the levator ani group. This is the puborectalis, pubococcygeus, and iliococcygeus, and the coccygeus muscle. Together, they create a sling that supports the bladder, rectum, and reproductive organs.

There are also important neighbouring muscles that are not technically classed as pelvic floor muscles but have a direct influence on how it behaves. The obturator internus and piriformis are hip muscles, yet they share fascial and neural connections with the pelvic floor and can strongly affect pelvic tension, pain and coordination.

What does the pelvic floor actually do?

The pelvic floor is responsible for far more than most people realise.

Its most obvious role is organ support. It helps hold the bladder, uterus in those who have one, rectum, and parts of the bowel in their intended positions and resists downward pressure that could otherwise lead to prolapse.

It also plays a key role in continence. Pelvic floor muscles contract reflexively and voluntarily to control the release of urine and stool, responding rapidly to changes in pressure when you cough, laugh or lift.

At the same time, these muscles have to be able to relax. Defecation requires the pelvic floor to lengthen and coordinate with the abdominal wall and diaphragm to allow stool to pass. A pelvic floor that cannot relax properly can be just as problematic as one that is weak.

Sexual function is another major role. Pelvic floor muscles contribute to arousal, sensation, and orgasm in all genders, and altered tone can significantly affect comfort and pleasure.

Less commonly discussed, but equally important, is the pelvic floor’s contribution to postural stability. It forms part of the deep core system alongside the diaphragm, deep abdominal muscles, and deep spinal muscles. Together, these structures help stabilise the trunk and pelvis during movement.

Finally, the pelvic floor is central to managing intra abdominal pressure. It works with the diaphragm and abdominal wall to regulate pressure during everyday tasks like breathing, lifting, and even speaking.

The pelvic floor and diaphragm connection

Think about the torso as a pressurised cylinder. The diaphragm is the roof, the pelvic floor forms the base the abdominal walls are the sides and the deep spinal muscles make up the back wall.

When you inhale the diaphragm contracts and moves downward. when things are well coordinated, the pelvic floor responds by gently lengthening to accommodate the increase in pressure. As you exhale the diaphragm rises and the pelvic floor reflexively recoils and contracts.

This rhythm matters. Habitual breath holding, chest dominant breathing or constant bracing can disrupt this relationship. Over time that disruption often shows up as excessive pelvic floor tension.

In people with hypermobility this pattern is very common. When joints feel unstable, the nervous system often responds by bracing and guarding. The pelvic floor as a stabiliser of the pelvis and hips frequently becomes part of that strategy.

How Hypermobility and EDS Affect the Pelvic Floor

The connective tissue connection

The pelvic floor does not rely on muscle alone. Its integrity depends heavily on connective tissue, particularly collagen (1). Ligaments such as the uterosacral and cardinal ligaments help suspend the uterus and vaginal vault, while the endopelvic fascia forms a supportive scaffold around all pelvic organs.

In EDS and hypermobility spectrum disorders, collagen is structurally different (1). It is often more elastic and less resilient than usual. This means the tissue that supports the pelvic organs is weaker from the outset. As a result, people with EDS or HSD may develop pelvic floor dysfunction even without classic risk factors such as pregnancy, childbirth, or ageing.

How common are pelvic floor problems in EDS and HSD?

A large scoping review published in 2020 analysed 105 studies looking at urogenital and pelvic complications in EDS and HSD (5). Pelvic floor problems were very common.

Urinary incontinence was reported at rates well above what is seen in the general population (5). Pelvic organ prolapse appeared across multiple studies often occurring at younger ages than expected (5). Dyspareunia, or pain with intercourse was frequently reported, with one study of 386 women with hypermobile EDS showing a 43 percent rate of dyspareunia alongside high rates of menorrhagia and dysmenorrhoea (6). Faecal incontinence and rectal prolapse were less common, however, still more prevalent than in non hypermobile populations (5).

The exact numbers vary widely due to differences in study design, sample size and EDS subtype. What is consistent however, is the overall pattern of elevated risk.

This trend is echoed in research on chronic pelvic pain. Among women presenting with myofascial pelvic pain, those with generalised hypermobility spectrum disorder were found to have significantly higher odds of coexisting symptoms. These included dyspareunia, low back pain, stress urinary incontinence, irritable bowel syndrome and hip pain when compared to nonhypermobile individuals (5).

Hypertonic versus hypotonic pelvic floors

This is one of the most important and most misunderstood pieces of the puzzle for people with EDS and HSD.

Pelvic floor dysfunction is not always about weakness. In fact, many hypermobile people have a hypertonic pelvic floor, meaning the muscles are overactive, guarded, and unable to fully relax.

A hypertonic pelvic floor is an increased resting muscle tone, either due to active contraction, passive stiffness, or both. High tone pelvic floor dysfunction has been reported in around 63 percent of patients presenting with chronic pelvic pain in large studies using structured diagnostic criteria (8).

When the pelvic floor is chronically tight, it can struggle to do its job properly. Fatigued muscles eventually fail to support organs effectively. Relaxation becomes difficult, contributing to constipation and painful intercourse. Urinary urgency(strong feeling of needing to pee), frequency, and incomplete emptying are common. Pain may also be referred to the hips, low back, abdomen, or thighs.

In hypermobility, this pattern often develops as a protective response. When ligaments and joint capsules are lax, the nervous system looks for stability elsewhere. Muscles are recruited to guard vulnerable areas, and the pelvic floor is a prime candidate. Over time, this guarding becomes the default state, and the muscles lose their ability to switch smoothly between contraction and relaxation.

A hypotonic pelvic floor, where the muscles are genuinely underactive and weak, also occurs in EDS and HSD. This is more likely after childbirth, with increasing age, or when connective tissue support is severely compromised. In these situations, strengthening may be appropriate.

The critical takeaway is this. Hypertonic and hypotonic pelvic floors can produce very similar symptoms. Both can be associated with incontinence, prolapse sensations, and pain. This is why blanket advice to “just do Kegels” can be unhelpful or even harmful. A proper assessment by a pelvic floor physiotherapist or physical therapist is essential before starting any exercise programme.

Specific Pelvic Floor Problems in EDS/HSD

Pelvic Organ Prolapse

Pelvic organ prolapse often shortened to POP, occurs when one or more pelvic organs descend from their usual position and press into or through, the vaginal or rectal walls. The specific presentation depends on which structure is involved.

A cystocele refers to the bladder dropping into the front wall of the vagina. A rectocele occurs when the rectum bulges into the back wall of the vagina. Uterine prolapse describes descent of the uterus into, or beyond, the vaginal canal. An enterocele involves the small intestine pressing against the upper vaginal wall. Rectal prolapse is slightly different, as the rectum itself protrudes through the anus.

In hypermobility and EDS, prolapse is not just a consequence of muscle weakness or childbirth. A systematic review and meta analysis by Veit Rubin found a statistically significant association between joint hypermobility and pelvic organ prolapse, although there was considerable variation between studies (9). More recently, a 2023 case series by Nazemi et al. presented three cases of prolapse in people with EDS, showing the need for earlier and more comprehensive evaluation, with the authors noting the importance of a multidisciplinary approach (10).

The underlying mechanism is mostly straightforward. When ligaments and fascia are made from collagen that is more elastic and less resilient, they cannot provide the same passive support to pelvic organs. Muscles can compensate for a time, but they cannot do the job of connective tissue indefinitely. Eventually, the system gives way.

Common symptoms include a feeling of pelvic heaviness or pressure, the sensation that something is “coming down” a visible or palpable bulge at the vaginal opening, lower back discomfort, difficulty fully emptying the bladder or bowel, and the need to splint or support the vaginal wall during bowel movements.

Constipation and gastrointestinal dysmotility

Constipation is one of the most frequently reported gastrointestinal complaints in EDS and HSD, and it is closely tied to pelvic floor function (5). Several mechanisms tend to overlap.

Collagen provides structural integrity to the gut wall, and abnormal collagen can alter the elasticity and tensile strength of the bowel. This can reduce the efficiency of peristalsis and slow transit. Autonomic dysfunction further complicates things, as the autonomic nervous system plays a central role in regulating gut motility. Dysautonomia which is common in EDS and HSD can impair coordination and slow movement through the digestive tract (4).

There is also growing interest in gut brain axis dysfunction. Both EDS and IBS appear to involve altered communication between the enteric nervous system and the central nervous system, which can amplify symptoms in both directions.

On top of this, pelvic floor dyssynergia is common. In this pattern, the pelvic floor muscles paradoxically contract instead of relaxing during a bowel movement, making evacuation difficult or even impossible.

When stool remains in the colon for too long it becomes harder and drier. Straining follows and that straining drives high downward pressure through the pelvic floor and pelvic organs. Over time, this increases the risk of prolapse and solidifies pelvic floor dysfunction. For this reason, addressing constipation is not optional. It is a foundational part of pelvic floor care.

Urinary dysfunction

Bladder symptoms are the most commonly reported urogenital issues in EDS and HSD (5). These can include stress urinary incontinence, where urine leaks during coughing, sneezing, laughing, or exercise, as well as urge incontinence with a sudden and difficult to defer need to urinate.

Many people also report increased urinary frequency, nocturia, hesitancy, a slow stream, and even the sensation of incomplete emptying. These difficulties are often linked to a hypertonic pelvic floor rather than weakness. Recurrent urinary tract infections can then follow, particularly when the bladder does not empty fully.

Across studies, rates of urinary incontinence in women with EDS and HSD are consistently higher than those seen in the general population (5). Bladder diverticula which are outpouchings of the bladder wall, are also reported more frequently than expected, again reflecting connective tissue vulnerability (5).

Sexual dysfunction

Sexual dysfunction is common in EDS and HSD, yet it is rarely discussed openly, often ignored. A study of 386 women with hypermobile EDS found high rates of dyspareunia, alongside heavy and painful periods (6).

Several factors tend to overlap. Hypertonic pelvic floor muscles may be unable to relax enough for comfortable penetration. Fragile connective tissue can contribute to vaginal dryness, tearing, and postcoital bleeding. Conditions such as vulvodynia and vestibulodynia may be present, potentially influenced by mast cell activity and nervous system sensitisation (7).

Joint pain and instability can make certain positions painful or impractical, while fatigue and widespread pain reduce desire and overall engagement, which makes sense as pain and fatigue aren’t exactly romantic.

Men with EDS and HSD are no exception. Pelvic floor related sexual dysfunction in men can include chronic prostatitis or chronic pelvic pain syndrome and erectile dysfunction. Mast cell activation may contribute through the release of histamine and other inflammatory mediators in genital tissues.

Chronic pelvic pain

Chronic pelvic pain which is defined as pain in the lower abdomen or pelvis lasting longer than six months, is extremely common in EDS and HSD (5). Rarely does it have a single cause. Hypertonic pelvic floor muscles, instability of the sacroiliac joints or pubic symphysis, central sensitisation and nociplastic pain, endometriosis, pelvic congestion syndrome, and referred pain from the hips, lumbar spine, or abdominal wall frequently coexist. These factors interact and reinforce one another, which is why diagnosis and treatment are often complex and why a multidisciplinary approach is usually necessary.

Related Conditions That Affect the Pelvic Floor

Autonomic dysfunction and POTS

The autonomic nervous system controls involuntary processes like heart rate, blood pressure, digestion, bladder function, and temperature. Autonomic dysfunction is common in EDS and HSD, with postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome being the most recognised presentation (4). POTS is defined by an excessive rise in heart rate on standing without a corresponding drop in blood pressure.

Autonomic dysfunction influences the pelvic floor in several ways. Bladder function is partly autonomically controlled so urgency, frequency, and voiding difficulty are common. Gut motility slows, contributing to constipation and IBS type symptoms. Heightened sympathetic or better known as “fight or flight” tone promotes chronic muscular tension, including in the pelvic floor. Over time, deconditioning driven by activity avoidance can further weaken coordination and endurance.

The link between EDS and POTS is thought to involve lax connective tissue in blood vessel walls, impairing vasoconstriction and leading to venous pooling, particularly in the abdomen and lower limbs (4). The autonomic nervous system compensates with increased heart rate and sympathetic output, often at a cost elsewhere.

Mast cell activation syndrome

Mast cells release histamine and other inflammatory mediators as part of the immune response. In mast cell activation syndrome these cells are triggered too easily and too often. The association with EDS is increasingly recognised, although the exact mechanisms remain under investigation (4).

MCAS is relevant to pelvic floor symptoms because mast cell mediators can drive inflammation in the bladder wall, vulva, and bowel. Heparin release may contribute to heavy menstrual bleeding. Histamine in vaginal tissue can worsen vaginitis and dyspareunia. Systemic activation can also exacerbate autonomic symptoms, creating a feedback loop with POTS.

While research specifically linking MCAS treatment to pelvic floor outcomes is limited, targeted management with antihistamines and mast cell stabilisers may improve some pelvic symptoms in clinical practice.

Anxiety and the brain body connection

The relationship between hypermobility and anxiety is one of the most robust findings in this field. Hypermobile individuals have been shown to have around a four times increased risk of anxiety compared with the general population (11). One study has shown that those with hypermobility have significantly larger bilateral amygdala volumes compared with non hypermobile controls (12), and a subsequent fMRI study by the same group demonstrated heightened neural reactivity in the insular cortex during emotional processing, with interoceptive sensitivity mediating the relationship between hypermobility and anxiety (13).

This points toward altered interoception, the sense of internal bodily states. In hypermobility, signals from the body, such as a slightly elevated heart rate from POTS, may be amplified and interpreted as threatening. The result is a feedback loop of autonomic arousal, heightened bodily awareness, anxiety, and further arousal.

For the pelvic floor, this has direct consequences. Anxiety drives chronic bracing and guarding, increases urinary urgency and frequency and is strongly associated with IBS. Fear of pain can lead to movement avoidance, deconditioning, and worsening symptoms over time.

Central Sensitisation and Nociplastic Pain

One of the most important concepts to understand in persistent pelvic pain is central sensitisation. Where the central nervous system becomes overly responsive, amping up sensory input so that signals which would not normally be painful are experienced as pain. Central sensitisation is now widely recognised as a key driver in many chronic pelvic pain conditions, including interstitial cystitis, vulvodynia, irritable bowel syndrome, and chronic prostatitis (14).

The clinical term used to describe pain arising primarily from this mechanism is nociplastic pain (14). Rather than being driven by ongoing tissue damage or inflammation, nociplastic pain reflects changes in how the nervous system processes and interprets signals. Research has shown that higher levels of nociplastic pain are associated with greater pelvic pain severity, more frequent symptoms, and a larger impact on daily life (15).

This becomes more relevant in people with pelvic floor dysfunction. In one large study, individuals with high tone pelvic floor dysfunction showed significantly higher levels of nociplastic pain and more widespread pain compared with those without high tone dysfunction (8). In other words, a persistently overactive pelvic floor does not just hurt locally. It can drive changes in the nervous system that make pain more diffuse, persistent, and harder to settle.

This matters because if central sensitisation is a major contributor to someone’s symptoms, treatments that focus only on local tissues may fall short. Exercises, injections, or even surgery may provide limited relief if the nervous system itself remains sensitised. More effective management often needs to include strategies that calm and retrain the nervous system, such as pain neuroscience education, graded exposure to movement, mindfulness based approaches, and in some cases medications that modulate central pain processing.

Proprioceptive deficits

One of the more common things I hear is “I can’t tell if I’m even doing anything down there” I worked with a client once who when they went for tests watched their own pelvic floor biofeedback screen and burst out laughing because the graph showed a massive contraction while they felt relaxed. When they tried to contract the muscle the graph barely changed, it wasn’t a lack of effort. The brain simply didn’t have an accurate map of what the pelvic floor was doing.

Proprioception is the body’s ability to sense its position and movement in space. It is something most people take for granted until it stops working well. In EDS and HSD, proprioception is frequently impaired. One study found that people with hypermobile EDS were significantly less precise than healthy controls when estimating the position of their hand, showing twice the variability in their responses, and that this imprecision was directly related to the severity of their joint hypermobility (16).

When we bring this back to the pelvic floor, the implications are significant. Impaired proprioception can make it difficult to sense pelvic floor muscle activity at all, let alone coordinate it effectively. This makes learning how to do exercises harder, particularly when the instructions are not clear or relies on internal awareness alone.

Reduced proprioception can also interfere with the ability to time pelvic floor contraction and relaxation during real life tasks such as lifting, coughing, or having a bowel movement. Many people become more reliant on visual or tactile feedback, including mirrors, hands on guidance, or biofeedback devices, during rehabilitation. On a broader level, proprioceptive deficits can increase clumsiness and fall risk, which may indirectly place more strain through the pelvis and pelvic floor over time.

Pregnancy, Childbirth, and the Postpartum Pelvic Floor

Pregnancy in EDS and HSD

Pregnancy places extraordinary demands on connective tissue. In a typical pregnancy, hormones such as relaxin increase tissue elasticity to allow the pelvis to adapt for birth. In EDS and HSD, this hormonal effect is layered on top of tissue that is already more compliant than average.

Population level data reflects this added vulnerability. A large population based study using national inpatient data found that people with EDS were more likely to undergo caesarean section & experience postpartum haemorrhage, have intrauterine growth restriction and deliver prematurely compared with non EDS controls (17). Pelvic girdle pain during pregnancy is also commonly reported in EDS and often begins earlier than would usually be expected.

More recently, a 2024 scoping review and expert co creation study published in PLoS ONE developed evidence guidelines for managing pregnancy, birth and the postpartum period in hEDS and HSD (18). Key recommendations included individualised birth planning, tailored pain management strategies, awareness of tissue fragility and tear risk, routine postpartum pelvic health follow up, and a multidisciplinary approach that considers dysautonomia, mast cell activation and mental health.

Childbirth considerations

During labour and delivery, people with hEDS or HSD may experience a number of specific challenges. Rapid or precipitate labour is not uncommon and may increase the risk of perineal tearing (18). Severe tears and delayed wound healing are reported more frequently, as is postpartum haemorrhage (17). Joint related complications such as pubic symphysis separation or coccyx injury can also occur.

Prolapse risk may increase due to the combined effects of pregnancy weight, pushing, and connective tissue vulnerability. Anaesthesia requires careful consideration as well. Epidurals may exacerbate POTS related hypotension, and prolonged Valsalva manoeuvres during pushing can worsen haemodynamic instability.

Vaginal delivery is not contraindicated in hypermobile EDS, but decisions should always be individualised (18). Some authors recommend timely episiotomy when indicated to reduce uncontrolled tearing, meticulous perineal repair by experienced clinicians, and active management of the third stage of labour to reduce haemorrhage risk (18).

Postpartum recovery

After delivery, the pelvic floor in someone with EDS or HSD often needs more support than standard advice provides. Blanket instructions to “just do your Kegels” can be inappropriate, particularly if the pelvic floor has become hypertonic during pregnancy as a protective guarding response.

A thorough postpartum assessment by a pelvic floor physiotherapist is strongly recommended before starting any exercise programme. For this population, postpartum pelvic health follow up should be routine rather than exceptional (18).

Men and Pelvic Floor Dysfunction in EDS and HSD

Pelvic floor dysfunction is not exclusively a female issue. Men, and people assigned male at birth, with EDS or HSD can experience a wide range of pelvic floor related symptoms. These include chronic prostatitis or chronic pelvic pain syndrome, urinary incontinence and voiding dysfunction, faecal incontinence, sexual dysfunction such as erectile difficulties or pain during or after ejaculation, and chronic pelvic pain.

Despite this, research on men’s pelvic health in EDS is sparse. In the scoping review by Gilliam and colleagues, only around 7 percent of included studies reported on male specific complications (5). This lack of visibility often leaves men underdiagnosed and undertreated. The underlying principles of assessment and treatment, however, are fundamentally the same, and men should feel empowered to seek care from a pelvic floor physiotherapist.

Recognising Pelvic Floor Dysfunction

Symptoms to watch for

According to the International Urogynecological Association and International Continence Society, pelvic floor dysfunction can present with a wide range of symptoms (19). These include urinary incontinence of any type, increased urgency or frequency, nocturia, difficulty emptying the bladder, symptoms of pelvic organ prolapse such as heaviness or bulging, sexual dysfunction, faecal incontinence or urgency, constipation or obstructed defecation, lower urinary tract pain, chronic pelvic pain, and recurrent urinary tract infections (19).

Why diagnosis is tricky in EDS and HSD

One of the biggest challenges in EDS and HSD is that hypertonic and hypotonic pelvic floors can look remarkably similar on the surface. Someone with a hypertonic pelvic floor may leak urine, not because their muscles are weak, but because those muscles are so fatigued from constant over contraction that they cannot respond when needed.

This is a common story in hypermobility clinics. People are prescribed standard pelvic floor strengthening exercises, follow them diligently, and watch their symptoms worsen. In most cases, the missing piece is unrecognised hypertonicity.

Assessment methods

A proper evaluation should be comprehensive. It should include a detailed history covering symptom onset, bowel and bladder habits, sexual function, obstetric history, and EDS or HSD related features. External and internal pelvic floor examination remains the gold standard and should be performed by a trained pelvic floor physiotherapist to assess tone, strength, endurance, coordination, and tenderness.

Additional investigations can include urodynamic testing to assess bladder storage and emptying, and anorectal manometry to evaluate rectal and anal sphincter pressures. Interestingly though, research in people with HSD and hEDS has shown that anorectal pressure profiles may not differ significantly from controls, suggesting that musculoskeletal and neuromuscular factors may sometimes play a larger role than connective tissue pathology alone (20).

Imaging such as pelvic floor ultrasound or dynamic MRI can also be useful for identifying structural issues including prolapse, muscle defects or abnormal descent during straining.

Management and Treatment

Managing pelvic floor dysfunction in EDS and HSD looks different from standard care. What works well for the general population can easily miss the mark here, or even make symptoms worse. The aim is not to do more, but to do things differently, with a clearer understanding of connective tissue, the nervous system and how the whole body fits together.

Principles of treatment

There are a few guiding principles that consistently matter.

First assess before you treat. It is never safe to assume that the pelvic floor needs strengthening. The problem may be excessive tension, poor coordination, low tone, or a mix of all three. Getting this wrong can cause a set back of months.

Secondly, you should treat the whole person. Pelvic floor dysfunction in EDS and HSD rarely exists in isolation. Autonomic dysfunction, gut symptoms, pain sensitisation, anxiety, and joint instability all interact with the pelvic floor. Ignoring these pieces limits progress.

Thirdly, be gentle and gradual. Fragile tissue and a sensitised nervous system mean that aggressive approaches often backfire. Graded exposure, starting at very low intensity and progressing slowly, is not optional here.

It is also important to avoid unhelpful bracing cues. Instructions like “pull in your abs” or “activate your core” often increase global tension and worsen pelvic floor hypertonicity. Instead, the focus should be on timing, coordination, and the ability to both contract and fully relax.

Finally, prioritise relaxation when it is needed. For hypertonic pelvic floors, learning to lengthen and release the muscles comes first. Strengthening only makes sense once resting tone has normalised.

Pelvic floor physiotherapy

Pelvic floor physiotherapy is the cornerstone of conservative management and should usually be first line treatment. A clinical commentary on managing patients with hEDS and HSD highlights several key components (21).

These include hands on therapy to address restrictions in the muscular and fascial system that influence the pelvic floor. Carefully graded strengthening and stabilisation starting with gentle isometrics and attention to posture and movement patterns that may be perpetuating symptoms. Functional retraining, flare management strategies, and clear education are just as important as exercises themselves. Collaboration with other healthcare professionals is often essential.

Experience matters. Therapists need to understand connective tissue disorders and be willing to adapt standard protocols. Many people with EDS and HSD carry a long history of being dismissed, gaslit or misunderstood so a validating trauma informed approach is not a luxury. It is crucial.

Biofeedback

Biofeedback uses sensors to provide real time visual or auditory information about pelvic floor muscle activity. For people with EDS and HSD, this can be particularly valuable.

Proprioceptive deficits often make it difficult to tell whether the pelvic floor is contracting or relaxing at all. Biofeedback helps bridge that gap. It is especially useful for down training, learning to recognise and release excessive tension. Objective feedback can also make progress visible, which is motivating when symptoms fluctuate.

Biofeedback has demonstrated benefit in conditions such as dyssynergic defecation, chronic constipation, and faecal incontinence, where coordination rather than strength is the primary issue (22).

Breathwork and diaphragmatic breathing

Because the diaphragm and pelvic floor move together, breathing patterns have a direct influence on pelvic floor function.

Learning diaphragmatic breathing, where the ribcage and abdomen expand rather than the chest lifting, can help reduce chronic pelvic floor tension. Coordinating breath with pelvic floor movement, inhaling as the pelvic floor lengthens and exhaling as it gently recoils, can restore more normal synergy. Breathwork also helps reduce the bracing and guarding patterns that are common in EDS and HSD.

There is an important nuance here. A 2023 systematic review by Bø, Driusso, and Jorge found that pelvic floor muscle training was significantly more effective than breathing exercises alone for improving urinary incontinence and prolapse and that adding breathing exercises to pelvic floor training did not improve these specific outcomes (23). This does not mean breathing is unimportant. It means breathing should support pelvic floor work and not replace it. For hypertonic pelvic floors, breathwork is often a necessary first step before any strengthening begins.

Pessaries

Pessaries are removable silicone or rubber devices inserted into the vagina to support prolapsed organs. They are considered a first line nonsurgical option for pelvic organ prolapse and can provide meaningful symptom relief.

They are particularly relevant for people with EDS and HSD who want to avoid or delay surgery, have increased surgical risk due to tissue fragility, are pregnant or postpartum or need symptom relief while engaging in physiotherapy.

Pessaries must be professionally fitted, and follow up is a must. Possible complications include discharge, discomfort, erosion, or bleeding, though these are usually manageable. In EDS, mucosal fragility means fitting often requires extra care and topical oestrogen may help improve tissue tolerance where appropriate.

Lifestyle and dietary strategies

Simple strategies can make a significant difference when applied consistently.

Good hydration and fibre intake are fundamental for preventing constipation and reducing straining. Aiming for around 25 to 30 grams of fibre per day is often recommended.

Toileting posture also matters. Elevating the feet on a step stool places the puborectalis muscle in a more relaxed position and can make bowel movements easier.

Avoiding heavy lifting where possible helps reduce pelvic floor load. When lifting cannot be avoided, learning to coordinate breath and movement is key. Managing body weight can reduce chronic intra abdominal pressure. For bladder symptoms, avoiding excessive fluid restriction, reducing irritants such as caffeine and alcohol, and using timed voiding strategies may help.

Addressing central sensitisation

When nociplastic pain plays a major role, pelvic floor work alone is rarely enough.

Pain neuroscience education can reduce fear and change how pain is interpreted. Graded motor imagery and graded exposure help reintroduce movement and activities that have become linked with pain. Mindfulness based approaches have evidence in chronic pain management, and cognitive behavioural therapy can be particularly helpful when pain and anxiety are tightly linked.

In some cases, medications that modulate central pain processing, such as low dose amitriptyline, duloxetine, or gabapentin, may be appropriate. These should be prescribed by clinicians familiar with EDS and HSD. Sleep also deserves attention. Poor sleep amplifies central sensitisation, so improving sleep quality is a core part of pain management.

Exercise and rehabilitation beyond the pelvic floor

The pelvic floor does not exist in isolation, and neither should rehabilitation.

A systematic review of exercise and rehabilitation in EDS found that strengthening programmes, proprioceptive training, and gentle stretching can improve pain, function, and quality of life (24). Effective programmes tend to start with isometrics, progress through multiple joint angles, and only later move into isotonic exercises.

Moderate intensity aerobic exercise supports cardiovascular health, pain modulation, and autonomic regulation, but it must be carefully graded to avoid symptom flares. Proprioceptive training, balance work or controlled use of unstable surfaces, can improve joint position sense and reduce injury risk. Compression garments may provide additional sensory feedback, improving body awareness.

so, it is important to remember that, the pelvis connects the hips, spine, and ribcage. Addressing strength and movement in surrounding regions can greatly influence pelvic floor function.

Surgical considerations

Surgery for pelvic floor dysfunction in EDS and HSD is generally a last resort. Tissue fragility increases the risk of intraoperative complications, suture failure, and delayed healing. Recurrence rates are higher in connective tissue disorders, and complications such as mesh erosion, chronic pain, or small bowel obstruction have been reported, including in documented cases following sacrohysteropexy (25).

Central sensitisation also matters here. If pain is primarily driven by nervous system amplification, surgery may not address the core problem.

When surgery is necessary, it should be performed by an experienced surgeon, ideally a urogynecologist familiar with EDS. Techniques must be adapted for tissue fragility, and both preoperative and post operative pelvic floor physiotherapy are essential for optimising outcomes.

Emerging therapies

A number of emerging approaches are being explored. Platelet rich plasma has shown some theoretical potential for connective tissue support, but evidence for pelvic floor applications remains preliminary. Custom 3D printed pessaries may improve fit and comfort for some individuals. Hormone releasing pessaries combine mechanical support with local oestrogen delivery. Targeted treatment of mast cell activation, using mast cell stabilisers and antihistamines, may improve pelvic symptoms where MCAS is a contributing factor, although pelvic floor specific research is still limited.

Building Your Care Team

Managing pelvic floor dysfunction alongside EDS or HSD is rarely something one practitioner can handle alone. These conditions sit at the corners of connective tissue, the nervous system, pain processing, and multiple organ systems. Because of that, care works best when it is shared.

At the centre of most care teams is a pelvic floor physiotherapist or physical therapist. This is usually the key provider and often the person who helps connect the dots between symptoms. Experience with connective tissue disorders matters here, as standard pelvic floor protocols often need aware and thoughtful adjustment.

Depending on your symptoms, other professionals can play important roles. A urogynecologist or urologist can assess prolapse, bladder dysfunction, and discuss surgical options when needed. A rheumatologist or geneticist may be involved in diagnosis, monitoring and ruling out other related conditions. Gastroenterologists are often essential when constipation, gut dysmotility, or IBS symptoms are prominent.

When pain has become persistent or widespread, a pain specialist can help address central sensitisation and guide medication or non pharmacological strategies. Psychologists or psychiatrists can support anxiety, trauma, and the emotional toll of living with chronic illness all of which directly influence pelvic floor function. Dietitians are invaluable for constipation management and nutritional support particularly when GI symptoms limit food choices.

In contrast to more straightforward pelvic floor presentations, autonomic symptoms often need their own expertise. An autonomic specialist or cardiologist can help manage POTS and related issues. If mast cell activation is suspected input from an allergist or immunologist may also be important.

When looking for providers, it is reasonable to ask directly about experience with EDS or HSD. Not every clinician will be familiar, and that is not a personal failing, however it does affect care. Advocacy organisations and patient communities can be helpful for finding practitioners who understand these conditions and take symptoms seriously.

The goal is not to build the biggest team possible, but the right one for you. Care works best when providers communicate, respect each other’s roles, and see you as a whole person rather than a collection of disconnected symptoms.

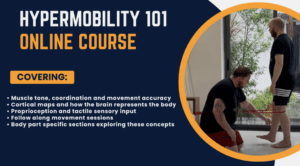

Enjoying Our Resources? Why Stop Here?

If you’ve found value in our posts, imagine what you’ll gain from a structured, science backed course designed just for you. Hypermobility 101is your ultimate starting point for building strength, stability, and confidence in your body.

References

(1) Malfait, F., Francomano, C., Byers, P., Belmont, J., Berglund, B., Black, J., Bloom, L., Bowen, J.M., Brady, A.F., Burrows, N.P., Castori, M., Cohen, H., Colombi, M., Demirdas, S., De Backer, J., De Paepe, A., Fournel-Gigleux, S., Frank, M., Ghali, N., Giunta, C., Grahame, R., Hakim, A., Jeunemaitre, X., Johnson, D., Juul-Kristensen, B., Kapferer-Seebacher, I., Kazkaz, H., Kosho, T., Lavallee, M.E., Levy, H., Mendoza-Londono, R., Pepin, M., Pope, F.M., Reinstein, E., Robert, L., Rohrbach, M., Sanders, L., Sobey, G.J., Van Damme, T., Vandersteen, A., van Mourik, C., Voermans, N., Wheeldon, N., Zschocke, J. and Tinkle, B. (2017) ‘The 2017 international classification of the Ehlers-Danlos syndromes’, American Journal of Medical Genetics Part C: Seminars in Medical Genetics, 175(1), pp. 8–26.

(2) Castori, M., Morlino, S., Celletti, C., Ghibellini, G., Bruschini, M., Grammatico, P., Blundo, C. and Camerota, F. (2013) ‘Re-writing the natural history of pain and related symptoms in the joint hypermobility syndrome/Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, hypermobility type’, American Journal of Medical Genetics Part A, 161A(12), pp. 2989–3004.

(3) Demmler, J.C., Atkinson, M.D., Mayberry, E.J., Sherwood, R.A., Thomas, M.F., Williams, E.J. and Lyons, R.A. (2019) ‘Diagnosed prevalence of Ehlers-Danlos syndrome and hypermobility spectrum disorder in Wales, UK: a national electronic cohort study and case-control comparison’, BMJ Open, 9(11), e031365.

(4) Kohn, A. and Chang, C. (2020) ‘The relationship between hypermobile Ehlers-Danlos syndrome (hEDS), postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome (POTS), and mast cell activation syndrome (MCAS)’, Clinical Reviews in Allergy & Immunology, 58(3), pp. 273–297.

(5) Gilliam, E., Hoffman, J.D. and Yeh, G. (2020) ‘Urogenital and pelvic complications in the Ehlers-Danlos syndromes and associated hypermobility spectrum disorders: a scoping review’, Clinical Genetics, 97(1), pp. 168–178.

(6) Hugon-Rodin, J., Lebègue, G., Becourt, S., Hamonet, C. and Gompel, A. (2016) ‘Gynecologic symptoms and the influence on reproductive life in 386 women with hypermobility type Ehlers-Danlos syndrome: a cohort study’, Orphanet Journal of Rare Diseases, 11(1), p. 124.

(7) Glayzer, J.E., McFarlin, B.L., Castori, M., Suarez, M.L., Meinel, M.C., Kobak, W.H., Steffen, A.D. and Schlaeger, J.M. (2021) ‘High rate of dyspareunia and probable vulvodynia in Ehlers-Danlos syndromes and hypermobility spectrum disorders: an online survey’, American Journal of Medical Genetics Part C: Seminars in Medical Genetics, 187(4), pp. 599–608.

(8) Till, S.R., Schrepf, A., Arewasikporn, A., Kratz, A.L., Missmer, S.A. and As-Sanie, S. (2025) ‘Data-driven diagnosis and clinical presentation of high-tone pelvic floor dysfunction’, American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, epub ahead of print 17 December 2025.

(9) Veit-Rubin, N., Singh, A., Engel, A., Goulart, C., Koenig, I., Chassagne, S., Cartwright, R. and Khullar, V. (2016) ‘The association between joint hypermobility and pelvic organ prolapse in women: a systematic review and meta-analysis’, International Urogynecology Journal, 27(Suppl 1), pp. S85–S86.

(10) Nazemi, A., Shapiro, K., Nagpal, S., Rosenblum, N. and Brucker, B.M. (2023) ‘Pelvic organ prolapse in Ehlers-Danlos syndrome’, BioMed Research International, 2023, article 6863711.

(11) Smith, T.O., Easton, V., Bacon, H., Jerman, E., Armon, K., Poland, F. and Macgregor, A.J. (2014) ‘The relationship between benign joint hypermobility syndrome and psychological distress: a systematic review and meta-analysis’, Rheumatology, 53(1), pp. 114–122.

(12) Eccles, J.A., Beacher, F.D., Gray, M.A., Jones, C.L., Minati, L., Harrison, N.A. and Critchley, H.D. (2012) ‘Brain structure and joint hypermobility: relevance to the expression of psychiatric symptoms’, The British Journal of Psychiatry, 200(6), pp. 508–509.

(13) Eccles, J.A., Owens, A.P., Mathias, C.J., Umeda, S. and Critchley, H.D. (2014) ‘Neuroimaging and psychophysiological investigation of the link between anxiety, enhanced affective reactivity and interoception in people with joint hypermobility’, Frontiers in Psychology, 5, p. 1162.

(14) Nijs, J., Lahousse, A., Kapreli, E., Bilika, P., Saraçoğlu, İ., Malfliet, A., Coppieters, I., De Baets, L., Leysen, L., Roose, E., Clark, J., Voogt, L. and Huysmans, E. (2023) ‘Nociplastic pain and central sensitization in patients with chronic pain conditions: a terminology update for clinicians’, Brazilian Journal of Physical Therapy, 27(3), p. 100518.

(15) Till, S.R., Schrepf, A., Engström-Melnyk, J., As-Sanie, S. and Harris, R.E. (2023) ‘Association between nociplastic pain and pain severity and impact in women with chronic pelvic pain’, The Journal of Pain, 24(10), pp. 1951–1960.

(16) Clayton, H.A., Jones, S.A.H. and Henriques, D.Y.P. (2015) ‘Proprioceptive precision is impaired in Ehlers-Danlos syndrome’, SpringerPlus, 4, p. 323.

(17) Alrifai, N., Alhuneafat, L., Jabri, A., Khalid, M.U., Tieliwaerdi, X., Sukhon, F., Hammad, N., Al-Abdouh, A., Mhanna, M., Siraj, A. and Sharma, T. (2023) ‘Pregnancy and fetal outcomes in patients with Ehlers-Danlos syndrome: a nationally representative analysis’, Current Problems in Cardiology, 48(7), p. 101634.

(18) Pezaro, S., Pearce, G., Engel, L., Genser-Medlitsch, M., Grahame, R., Hakim, A., Keen, R., Palmer, S., Skivington, K., Simmonds, J.V. and Tinkle, B. (2024) ‘Management of childbearing with hypermobile Ehlers-Danlos syndrome and hypermobility spectrum disorders: a scoping review and expert co-creation of evidence-based clinical guidelines’, PLoS ONE, 19(5), e0302401.

(19) Haylen, B.T., de Ridder, D., Freeman, R.M., Swift, S.E., Berghmans, B., Lee, J., Monga, A., Petri, E., Rizk, D.E., Sand, P.K. and Schaer, G.N. (2010) ‘An International Urogynecological Association (IUGA)/International Continence Society (ICS) joint report on the terminology for female pelvic floor dysfunction’, Neurourology and Urodynamics, 29(1), pp. 4–20.

(20) Zhou, W., Zikos, T.A., Halawi, H., Sheth, V.R., Gurland, B., Nguyen, L.A. and Neshatian, L. (2022) ‘Anorectal manometry for the diagnosis of pelvic floor disorders in patients with hypermobility spectrum disorders and hypermobile Ehlers-Danlos syndrome’, BMC Gastroenterology, 22, p. 538.

(21) Signorino, J., Bikkers, S. and Divine, K. (2024) ‘An evidence-based clinical commentary for treating patients with hypermobile Ehlers-Danlos syndrome or a hypermobility spectrum disorder’, Orthopaedic Physical Therapy Practice, 36(3).

(22) Rao, S.S.C. and Patcharatrakul, T. (2016) ‘Diagnosis and treatment of dyssynergic defecation’, Journal of Neurogastroenterology and Motility, 22(3), pp. 423–435.

(23) Bø, K., Driusso, P. and Jorge, C.H. (2023) ‘Can you breathe yourself to a better pelvic floor? A systematic review’, Neurourology and Urodynamics, 42(6), pp. 1254–1279.

(24) Buryk-Iggers, S., McGillis, L., Engert, J., Engert, V., Clarke, H. and Glendon, K. (2022) ‘Exercise and rehabilitation in people with Ehlers-Danlos syndrome: a systematic review’, Archives of Rehabilitation Research and Clinical Translation, 4(2), p. 100189.

(25) Simillis, C., James, O., Gill, K. and Zhang, Y. (2019) ‘Generalised peritonitis from strangulated small bowel obstruction secondary to mesh erosion: a rare long-term complication of laparoscopic mesh sacrohysteropexy’, BMJ Case Reports, 12(5), e226309.