- POTS and Exercise: The First Step Everyone Misses - 27 June 2025

- The Missing Link Between Breathlessness, Fatigue, and Chronic Pain: Understanding CO₂ Tolerance - 19 June 2025

- What is Mast Cell Activation Syndrome? - 12 May 2025

Is stretching good for hypermobility?

This seems like a fairly simple question, which should have a fairly simple answer, but does it?

If you want a subject that will make your head spin, then welcome to an area of life that is just fraught with myths and misinformation. Why can some people stretch with hypermobility or Ehlers Danlos Syndrome and feel great, whilst others hate it or get injured?

Is yoga the devil’s work or is the devil in the details?

The myths surrounding hypermobility, & EDS in general, are shocking, and things only get more confusing when we throw stretching into the mix!

In an earlier post, we covered some of the various misconceptions and myths that surround hypermobility, including the not-so-important posture, Facia and the one that has my own personal hatred: that pesky weak core of yours!

Today, I want to address the one that probably gets the most attention other than “core stability” and I am of course talking about hypermobility and stretching.

I asked a little while ago on our various social media pages, whether people with hypermobility and Ehlers Danlos syndrome were stretching or not, and the reasons behind either choice. There was a good mixture of stretchers and non-stretchers. However, the reasons behind people’s choices were incredibly varied.

For stretching with hypermobility & EDS we had some of the following responses;

- The Physio told me not to.

- I stretch because I have short muscles.

- If I don’t stretch, I will get stiff.

- I don’t stretch, I don’t want to cause damage.

- I tried yoga once and had a flare-up, so I don’t stretch.

- I stretch before my strengthening exercises; I don’t want to be injured.

As you can see, that is a pretty big spectrum of reasons behind why people are/aren’t stretching with hypermobility.

People with hypermobility often get confused when it comes to stretching and rightly so!

The sheer amount of misinformation out there is astounding. I think the only possible way forward here, has to be by actually taking a look at what stretching is, more importantly, what it does.

This article covers:

ToggleUnderstanding Hypermobility vs Flexibility

It’s completely understandable to feel confused when people throw around terms like “hypermobility” and “flexibility” as if they mean the same thing. But here’s the truth—they don’t. And getting clear on the difference is one of the first steps toward actually making progress with your body.

Let me break it down for you.

Hypermobility refers to joints that can move beyond the normal range you’d expect, usually because of differences in connective tissue. Think of it more as something you’re born with rather than something you train for. It’s passive. You don’t have to do anything for your joints to go that far, they just do. That’s why it’s commonly seen in conditions like Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome or Hypermobility Spectrum Disorders.

On the flip side, flexibility is about how far your muscles and soft tissues can lengthen and allow you to control movement. It’s trainable. It’s active. It’s something you build with effort, through strength, control, and awareness. Flexibility is all about what you can actively do with your range, not what your joints can passively allow.

And here’s where things get tricky.

You can absolutely be hypermobile and still feel “tight” or “inflexible.” Sounds contradictory, right? But that tightness you feel, that tension, is usually your body trying to stabilise joints that it knows are a little too wobbly. Your muscles are doing their best to keep you safe, even if it means creating a sensation of stiffness.

That’s why traditional stretching routines, especially the long and passive kind, can be a recipe for disaster in hypermobile bodies. Sure, they might feel nice in the moment, but if you’re not also working on strengthening and proprioception, they often lead to more instability, not less.

So, if you’re hypermobile and constantly stretching because you feel tight, it’s worth asking: is your body actually lacking range, or is it using tightness as a shield?

Stretching for hypermobility and EDS

When it comes to hypermobility and stretching, the biggest argument that the community has presented for “Is stretching good for hypermobility” is that stretching is to lengthen tight/short tissue. Again this would be a good argument if it was true.

We know that stretching doesn’t change the tissue length. Most of the time tissue stiffness is a subjective feeling, pretty much unmeasurable and has more to do with the brain than the actual tissues.

Can stretching help you to “feel” looser? Most definitely.

Can it also backfire and cause more problems? Absolutely!

Most things in life are subjective and that’s because we are simply brains floating in a dark tank pulling in information from the outside of the world, processing it, and then projecting our own subjective view of the world.

There are many variables in how people process the information based on context, emotions or beliefs. If you have a bad history with stretching, then it’s fair to assume years of reinforcing that belief will cause an equally bad time, the next time.

It’s also important to note that “nociception” not to be confused with “pain receptors” that has been well and truly debunked, impair our ability to properly map our bodies.

Nociceptors are high threshold receptors that respond to noxious stimuli, meaning any extremes in pressure, temperature, stretch, inflammation, and vibration, will cloud the brain area representations of the area that nociception comes from.

So, if you have recently subluxated or dislocated your knees, you are going to be stretching a joint that the brain is finding very hard to locate and stabilise, which could easily lead to further injury.

Again, there is a lot going on with stretching, and it’s not just all physical. If stretching helped ease that bad back you had for a long time, then it gets reinforced as a useful thing for your toolbox.

The rest of the arguments for stretching are also a little flawed, especially when it comes to the famous trigger points! Something that’s never been proven to actually exist and with the main body of evidence is a little sketchy, to say the least. But, that’s another blog in itself!

As far as the other reasons to stretch including, it helps to prevent injury, reduces post-exercise soreness and it’s a good warm-up, the evidence simply shows it’s not true.

Types of Stretching and What the Evidence Really Says

If you’ve been trying to figure out which type of stretching is actually helpful for a hypermobile body, you’re not alone. The internet is overflowing with advice, but when you live in a body that moves a little differently, the rules start to change.

Let’s go through what each type of stretching actually is, what it does, and most importantly, what it means for those of us navigating hypermobility.

Static Stretching

This is the kind of stretching most of us were first introduced to. You hold a muscle in a lengthened position, usually for around 15 to 60 seconds. Simple enough. And yes, static stretching can increase flexibility. But here’s the thing, if you’re hypermobile, your ligaments already have a bit more give than most. Holding joints at their end range for extended periods can put extra pressure on structures that are already working overtime to stay stable. Without good muscle control, this kind of stretching can leave you feeling looser, but not necessarily in a good way.

Dynamic Stretching

Dynamic stretching is much more movement-based. Think slow, repetitive motions that move your joints through a comfortable range without holding anything at the end. This kind of stretching warms you up, gets your brain and body talking, and encourages muscle engagement. For hypermobile folks, this is often a much safer choice. It helps boost circulation and proprioception without yanking your joints into places they don’t feel safe in.

Active Stretching

Active stretching is a little different. You’re using your muscles to create the stretch, not relying on gravity or pulling yourself into a position. This kind of work does more than just lengthen tissue, it builds strength and control where you need it most. Instead of just hanging out at the edge of your range, you’re actually learning to own that space with control and support.

What Does the Research Say?

Studies suggest that dynamic and active stretching tend to be safer and more effective for those with hypermobility. They help you keep your range of motion, while also building the kind of muscular support that protects your joints.

That said, static stretching still has a place. If you have genuinely shortened muscles that need lengthening, then short, gentle holds can be helpful. But even then, we want to stay far away from pushing into the very limits of a joint’s range. That’s where trouble tends to start.

Approaches like proprioceptive neuromuscular facilitation (PNF) and controlled end-range training are also starting to gain traction. These combine both flexibility and strength work, and when done properly, they can help build real control at the edge of your range. Just make sure you’re working with someone who understands the unique challenges of hypermobility.

Practical Tips for Stretching Safely

If you’re stretching as part of your daily movement practice, here are a few things to keep in mind:

- Use dynamic stretching to warm up, focusing on smooth, controlled motions that stay within a comfortable range.

- Lean into active stretching to help build strength and control around unstable joints.

- Avoid long static holds, especially if they take you to the end of your range. It’s not about being bendier. It’s about being safer.

- Focus more on how you move, not how far you can move.

- And if you feel pain, instability, or a weird kind of discomfort during a stretch, stop. That’s your body’s way of waving a red flag.

So, is Stretching Good for Hypermobility & Ehlers Danlos syndrome?

Let’s be real. Stretching is not the miracle solution it was once thought to be, but that does not mean it has no value. Like most things with hypermobility, the answer is not black and white. It sits somewhere in the middle, and it depends entirely on how you do it.

We now know that stretching does not significantly lengthen tissues in the way people used to think. What it does do, especially with consistent practice, is improve your tolerance to stretch. It helps your nervous system get more comfortable with a position. Most of the improvements we see are actually down to changes in how your brain interprets sensation, not changes in the structure of your muscles or fascia.

But this is not bad news. In fact, it opens up a far more useful conversation about how stretching can support you when you are hypermobile.

When done mindfully, stretching does not make your joints looser. It does not cause instability if you are not forcing yourself into your end range or holding positions for too long. The kind of stretching that helps is the kind that focuses on movement quality, not just chasing more range.

Dynamic and active stretching are often the safest and most effective choices for hypermobile bodies. They help your brain build a better sense of where your limbs are in space. They encourage gentle muscle activation and give your nervous system a reason to feel safe and supported.

And that feeling of tightness you get, even when you are already very mobile? That often comes from your body trying to protect you. Stretching in the right way can help ease that feeling, especially when it is combined with other strategies that support joint control.

Stretching needs the Right Partners

If you want to protect and support your joints, stretching on its own is not enough. It needs to be part of a bigger picture that includes strength work and proprioceptive training. Strength provides the scaffolding that keeps your joints feeling secure. Proprioception is what helps your brain build trust in your body’s movements.

So if you are going to stretch, do it in a way that complements those things. Work on areas that feel genuinely tight. Use gentle, controlled movements. Focus on how your body feels, not how far it can go.

A personal experience of using stretching to improve cortical maps

Little Berrie was told she was extremely hypermobile and she should never, ever, stretch!

When it came to Berrie we used stretching as a one part of her framework to help improve those cortical maps, through sensory input to jump start stabilising her joints and as you can see her stability and movement has improved so much.

Something we would not have been able to do, had we not used some forms of stretching for its sensory benefits.

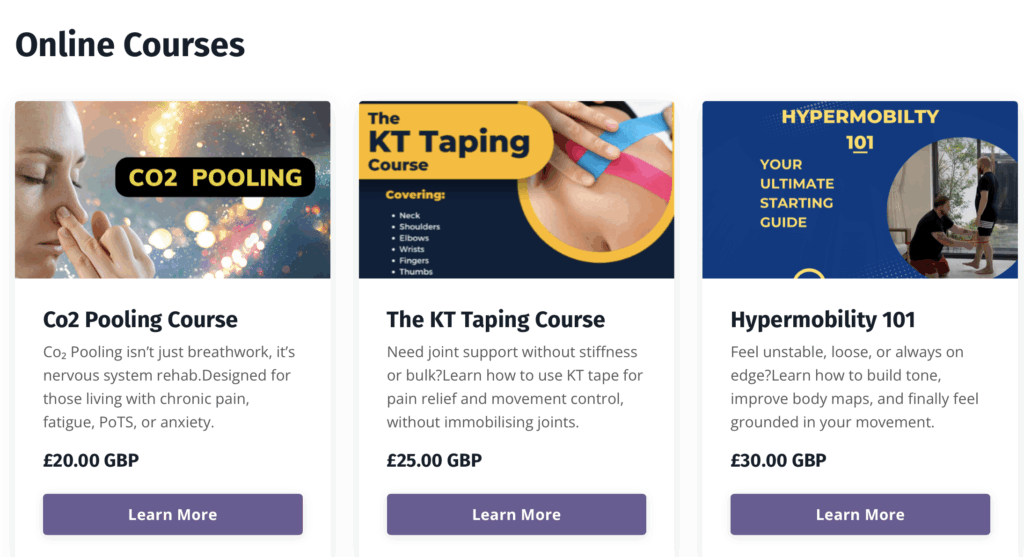

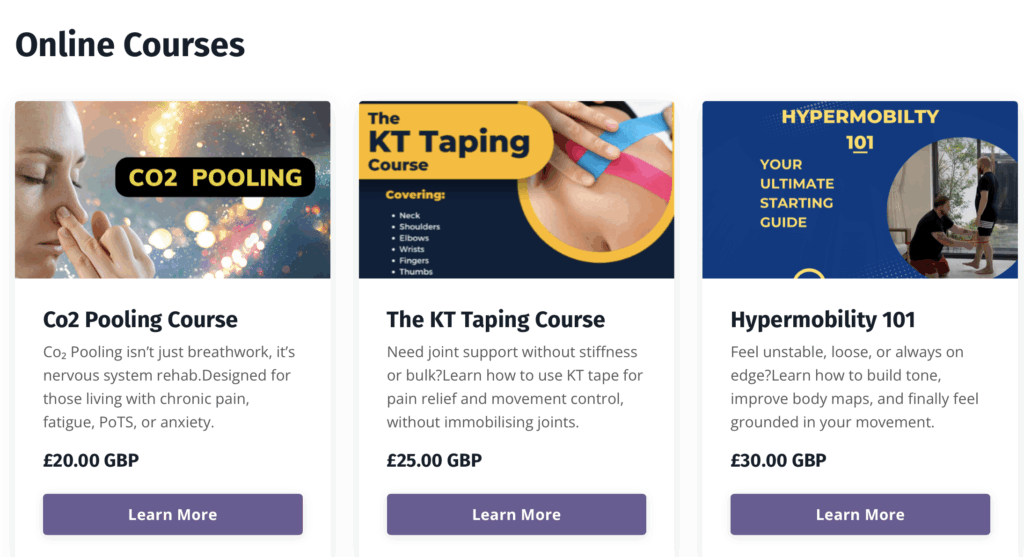

Enjoyed Our Blog? Why Stop Here?

If you’ve found value in our posts, imagine what you’ll gain from a structured, science-backed course designed just for you. Hypermobility 101 is your ultimate starting point for building strength, stability, and confidence in your body.

FAQ: Common Questions About EDS/Hypermobility and Stretching

It’s completely understandable to feel tight, even when your joints move more than they should. For many with hypermobility or Ehlers Danlos Syndrome, the muscles around a joint work overtime to keep things stable. This can lead to fatigue and the sensation of tightness. But more often than not, what you are feeling isn’t a true lack of flexibility, it’s a protective response.

Your nervous system is trying to keep you safe, and sometimes that means keeping muscles switched on to guard an unstable joint. We also have to consider central sensitisation, where the nervous system becomes more sensitive to input. Even mild sensations can feel amplified. Throw in postural imbalances and compensatory movement patterns, and it’s no surprise things start to feel stiff.

Stretching can be helpful, but only if it’s done with intention. Passive stretching, especially when held too long, can make unstable joints feel even less supported. That’s why we want to be smart about how we stretch.

Start by focusing on dynamic and active stretching. Dynamic stretching uses gentle movement to prepare the body for activity, while active stretching involves using your muscles to move into and hold the stretch. Both options are much safer than forcing a joint to the end of its range and holding it there.

Only stretch areas that actually feel restricted. Do not try to stretch everything. Avoid pain, and above all, pair any stretching you do with strengthening and proprioceptive work. This is what helps protect and stabilise your joints long term.

If you’re going to stretch, timing matters. Dynamic stretching is the safest choice before exercise. It helps your muscles warm up without putting your joints at risk. Save static or passive stretching for after strengthening, and only stretch areas that feel genuinely tight. Always listen to your body and prioritise stability over range.

One of the more confusing parts of living with EDS is figuring out if a muscle is genuinely tight or if it’s just protecting a joint. True muscle tightness often limits how far you can move and feels more mechanical. Guarding, on the other hand, is often a protective response and tends to ease with gentle movement, breathing, or reassurance.

If someone else can move the joint through a full range easily but you still feel tension, it’s likely not true tightness. It’s your nervous system stepping in to protect you. This is a common experience for those with Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome or hypermobility.

oga can absolutely be beneficial for EDS or hypermobility when it’s approached with the right mindset. The key is to avoid passive, deep stretching and any positions that involve locking or hanging out at the end of a joint’s range.

Choose slower, more controlled classes that encourage muscular engagement and awareness. Focus on building strength, not just increasing flexibility. If possible, work with instructors who understand hypermobility or Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome and are comfortable helping you modify poses to protect your joints..

Proprioception refers to your body’s ability to sense where it is in space. In EDS and hypermobility, this sense is often impaired, making movements feel unstable or unpredictable. That’s where proprioceptive training becomes a key part of any hypermobility or EDS management plan.

It helps retrain your brain to better sense and control your joints. This can reduce injury risk and improve coordination. Simple tools like balance pads, closed-chain movements, or gentle instability work can make a huge difference in your day-to-day movement confidence.

Yes, and many people with EDS actually do better when they use alternatives to traditional stretching. Techniques like foam rolling, gentle breathwork, massage balls, and relaxed movement can all reduce the sensation of tightness. These methods provide calming input to the nervous system and often improve body awareness, which is especially helpful if you struggle with proprioception.

You do not always need to lengthen a muscle to feel better. Sometimes, what your body really needs is reassurance, not range.

References:

Lauersen, J.B., Bertelsen, D.M., & Andersen, L.B. (2014). The effectiveness of exercise interventions to prevent sports injuries: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 48(11), 871–877.

De Weijer, V.C., Gorniak, G.C., & Shamus, E. (2003). The effect of static stretch and warm-up exercise on hamstring length over the course of 24 hours. Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy.

Malliaropoulos, N., Papalexandris, S., Papalada, A., & Papacostas, E. (2004). The role of stretching in rehabilitation of hamstring injuries: 80 athletes follow-up. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 38(3), 292–296.

Damasceno, M.V., Duarte, M., Pasqua, L.A., et al. (2014). Static stretching alters neuromuscular function and pacing strategy, but not performance during a 3-Km running time-trial. PLoS ONE, 9(9), e105059.

Folpp, H., Deall, S., Harvey, L.A., & Gwinn, T. (2006). Can apparent increases in muscle extensibility with regular stretch be explained by changes in tolerance to stretch? Australian Journal of Physiotherapy, 52(1), 45–50.

Beckett, J.R., Schneiker, K.T., Wallman, K.E., Dawson, B.T., & Guelfi, K.J. (2009). Effects of static stretching on repeated sprint and change of direction performance. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise, 41(5), 444–450.

Weppler, C.H., & Magnusson, S.P. (2010). Increasing muscle extensibility: a matter of increasing length or modifying sensation? Physical Therapy, 90(3), 438–449.

Hortobágyi, T., Faludi, J., Tihanyi, J., & Merkely, B. (1985). Effects of intense stretching-flexibility training on the mechanical profile of the knee extensors and on the range of motion of the hip joint. International Journal of Sports Medicine, 6(6), 317–321.

McHugh, M.P., Tallent, J., & Johnson, C.D. (2020). The role of neural tension in stretch-induced strength loss. Scandinavian Journal of Medicine & Science in Sports, 30(1), 3–12.

Ylinen, J., Kautiainen, H., Wiren, K., & Häkkinen, A. (2007). Stretching exercises vs manual therapy in treatment of chronic neck pain: a randomized, controlled cross-over trial. Journal of Rehabilitation Medicine, 39(2), 126–132.

Gómez-Hernández, M., Gallego-Izquierdo, T., Martínez-Merinero, P., et al. (2023). Benefits of adding stretching to a moderate-intensity aerobic exercise programme in women with fibromyalgia: a randomized controlled trial. Clinical Rehabilitation, 37(3), 331–342.

Chen, H.M., Wang, H.H., Chen, C.H., & Hu, H.M. (2015). Effectiveness of a stretching exercise program on low back pain and exercise self-efficacy among nurses in Taiwan: a randomized clinical trial. Pain Management Nursing, 16(3), 397–405.

Mizuno, T., Matsumoto, M., & Umemura, Y. (2013). Viscoelasticity of the muscle-tendon unit is returned more rapidly than range of motion after stretching. Scandinavian Journal of Medicine & Science in Sports, 23(1), 23–30.

Akkaya, K.U., et al. (2022). An investigation of body awareness, fatigue, physical fitness parameters, and musculoskeletal disorders in young adults with HSD. Rheumatology International, 42(5), 789–798.

Wilke, J., et al. (2024). The effects of static and dynamic stretching on deep fascia stiffness. Frontiers in Physiology, 15, 1288426.

Joint Hypermobility and Sport: A review of advantages and disadvantages. Available at: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24030301/