- POTS and Salt: What the Science Actually Says - 18 February 2026

- Why the Beighton Score Matters More Than It Should - 18 February 2026

- Brain Fog in EDS, POTS and Long COVID: Causes and Practical Ways to Cope - 13 February 2026

Every decade brings its own health and fitness trends. Some fade away quietly, and others dig their heels in. One that has managed to hang around far longer than it should have is the obsession with core exercises. And nowhere is this more apparent than in the world of hypermobility and Ehlers-Danlos syndrome.

Despite years of research painting a very different picture, the idea that a “weak core” is responsible for pain and injury still gets thrown around like fact. It’s plastered across blogs, repeated in fitness studios, and prescribed by well-meaning professionals who may not be up to date with the evidence.

Now, I’ve called core stability a myth before, and I still stand by that. At least in the way it’s been marketed. Because when you start peeling back the layers and look at what the research actually says, you start to see a much more complicated and far less dramatic story. You might expect a theory that came out of the late 90s and was based on a few very small studies to have quietly disappeared by now. But no, it continues to thrive.

And that’s a problem. Because when it comes to people with hypermobility, this old idea of core weakness doesn’t just miss the mark, it can actually do harm. Not necessarily because the exercises themselves are bad, but because they’re often used in ways that increase fear, encourage bracing, and promote a one-size-fits-all model that just doesn’t work.

But let’s be clear. Core exercises aren’t the villain. There is a time and a place where they absolutely have value. The issue is when we lose sight of the bigger picture. We need to stop throwing the whole body into chaos just to chase control over one small part of it.

So in this blog, we’re going to take a proper look at core stability. What it is. What it isn’t. What the science says. And what all of this means for your hypermobile pelvic floor, your joints, and your pain.

This article covers:

ToggleThe Issues around a hypermobility core stability

Let’s be honest, core stability is one of those terms that gets thrown around constantly but rarely with any real clarity. Most people hear it and immediately think of one muscle in particular, the transverse abdominis, or TVA. It’s the deepest of the abdominal muscles, and yes, it does have a role in stability. But the idea that it’s the single key to preventing pain or keeping everything in place doesn’t hold up.

Your core isn’t just one muscle. It’s a system made up of the pelvic floor, diaphragm, deep spinal muscles like the multifidus, and the TVA. These structures don’t work in isolation. They contract together and adapt based on what your body is doing. Standing still, walking, bending, reaching, or balancing all involve different recruitment patterns.

And most of it isn’t under conscious control. It’s driven by the nervous system. When your brain has a good map of your body and its position in space, it can call on the right muscles at the right time. That’s what real stability looks like. Not tensing your stomach. Not holding your breath. Not pulling your belly button in.

The whole idea that a weak TVA causes pain started from small studies back in the 90s. Researchers noticed a tiny delay in TVA activation in people with back pain. The muscle still fired. It just happened a little slower. Somehow that delay turned into a belief that the TVA was weak, or dysfunctional, or needed to be fixed. But the more recent research paints a different picture. It shows that while the TVA does play a role in stability, it’s part of a team. And that team’s effectiveness depends much more on coordination and timing than on strength alone.

This matters even more if you have hypermobility. With looser connective tissues, your body can’t rely on passive support like ligaments to hold things together. It has to rely more on active control, which means your brain and your muscles have to be in sync. And that’s not something you get from just doing crunches or clamshells. It comes from movement that teaches the body to work as a unit.

So, if someone’s told you that your core is weak and that it’s the reason you’re in pain, it’s completely understandable to believe it. That message has been repeated for years. But the evidence tells us it’s not the whole story. In fact, it may not even be the right story at all.

This is one of the most common beliefs we hear from clients, and one of the most persistent myths in the health and fitness world. The idea that a weak core causes pain, particularly lower back pain, has been repeated so often that it’s rarely questioned. But when we stop and actually look at what the research says, the story is a lot more complex.

Let’s start with something often used to back up this claim: pregnancy. During pregnancy, the abdominal wall stretches significantly, hormone levels like relaxin rise, and core stability is temporarily reduced. You could argue that during this time, someone has the most unstable core they will ever have. Yet, a large study that followed 869 postpartum women found that 635 of them recovered spontaneously from back pain within just one week, without any core-focused rehab at all.

Now, that doesn’t mean core strength isn’t important. But it does tell us that pain isn’t just about muscle strength. If it were, all of those women would still be in pain, but they’re not.

We see similar patterns after certain surgeries. In breast reconstruction, for example, surgeons often use a portion of the rectus abdominis, removing part of the abdominal wall structure altogether. That’s a pretty substantial hit to the core. And yet, there’s still no strong link between this type of surgical weakness and chronic back pain. Some people do experience discomfort or reduced function, but many don’t. Again, it’s not a simple cause and effect.

What the evidence shows is that core weakness can contribute to pain, particularly if it leads to more load being placed on passive structures like ligaments or spinal discs. But it’s not the sole cause, and it certainly isn’t the universal one it’s been made out to be.

In fact, much of the original theory behind core stability came from very small studies in the 1990s that noticed a tiny delay in transverse abdominis activation in people with back pain. That delay, measured in milliseconds, was never about weakness. The muscle still worked. It just fired slightly later. And later studies found mixed results, with some showing no delay at all.

This matters especially in hypermobility. People with EDS or HSD often have poorer proprioception, reduced passive stability, and muscle fatigue. Core training might help improve control and reduce strain, but not because the core is weak in the traditional sense. It’s more about restoring coordination and improving the body’s ability to respond to movement. That’s a neurological process as much as it is a muscular one.

And let’s not forget the psychosocial side of pain. Things like job stress, fear of movement, sleep, and general wellbeing play just as much of a role in chronic pain as anything physical. Research shows that pain is one of the biggest blind spots in medical training. One study found that over 80% of medical graduates lacked basic competency in pain management.

So, does a weak core cause pain?

Not by itself. It can contribute, especially in hypermobility where control matters more. But strengthening your core isn’t a guaranteed fix, and not having a perfect core doesn’t mean you’ll be in pain.

Pain is complex. Your approach to it should be too.

So why do people like core stability exercises?

So why do some people swear hypermobility core exercises work and why for some it does nothing?

As we mentioned before, pain is complex, and so is getting rid of it. And whilst a few studies do show that hypermobility core exercises can help with lower back pain, why don’t they work for everyone? What’s going on when we do core stability training?

Well, first off, we have the release of endorphins from exercises, we have noxious inhibitory control, we have the lessening of movement-related fear as you believe you are fixing an unstable core, and a multitude of other factors across the Biopsychosocial spectrum. When we look at the data, specific core stability exercises do seem to work marginally better for pain than just any old randomly selected exercise, and that’s most likely from interveining psychosocial factors such as breaking down the fear of movement and guarding.

However, there is no shortage of people out there, that through no fault of their own, core stability exercises have just not helped. Again, pain is complex and isn’t about just fixing one tiny thing. There are multitudes of factors that contribute to the creation of pain. Likewise, those with hypermobility, likely don’t have a great sense of proprioception, and may not perform the movement correctly leading to potential injury.

One issue I personally have with hypermobility rehab and indeed hypermobility core exercises, is that they promote segmenting the hypermobile body and focusing on solely one area. Many of the clients we see in the studio, all report the same systemic issues and the same treatment from health care professionals: they go for help with multiple dislocating joints, and at therapy, only one issue is addressed.

With Hypermobility rehab, these individuals need to relearn how to use the body as a unit again, and more of their rehab needs to lean toward the neurological side of things, not just joints and tissue. there is also the issue of these individuals being taught to brace and to contract their cores, which can lead to issues with the hypermobile pelvic floor.

Pelvic Floor Dysfunction and Hypermobility

There are many issues such as endometriosis, scoliosis, and especially pelvic floor dysfunction that rarely gets the attention it deserves when we talk about hypermobility and Ehlers-Danlos syndrome. Yet Pelvic floor issues, are incredibly common. In one study of over 1,300 women with EDS, more than half reported symptoms like stress incontinence, urgency, and even pelvic organ prolapse. Compared to the general population, those numbers are alarmingly high.

So what’s happening?

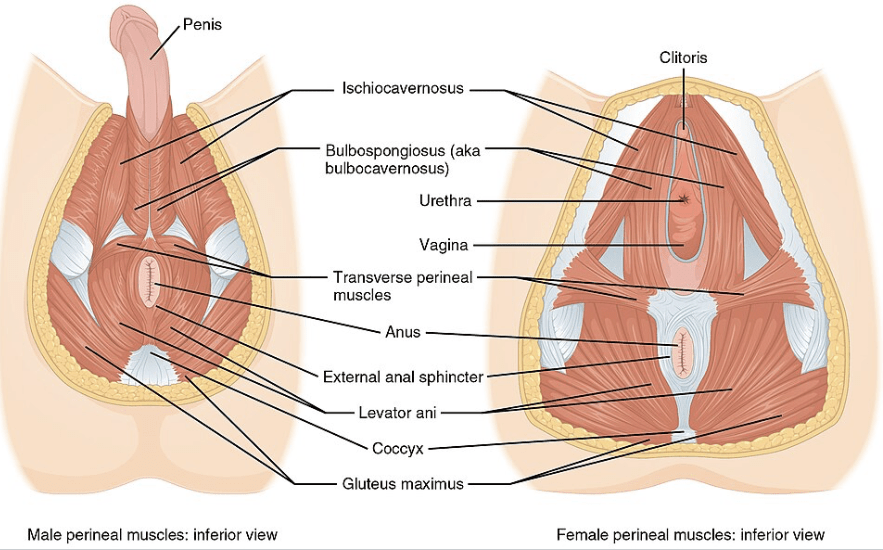

The pelvic floor is a network of muscles, ligaments, and connective tissues that supports the organs inside the pelvis. It also plays a major role in continence, postural control, and sexual function. In people with EDS or HSD, the collagen that holds this system together is more fragile. That lack of structural support means the muscles of the pelvic floor have to work harder just to keep things where they should be.

Sometimes these muscles become too tight. Other times they are weak or tired. Often, they simply don’t fire in the right way or at the right time. And this creates problems.

What many people don’t realise is that the pelvic floor is part of the core. It doesn’t work alone. It works with the diaphragm, the multifidus, and the transverse abdominis. These muscles contract together during movement and help regulate pressure inside the abdomen. This is why core stability training has become such a big part of pelvic floor rehab. The goal is to get everything working in sync again. One trial showed that combining pelvic floor muscle exercises with core stability training produced far better results than pelvic floor work alone. In that study, over 70 percent of participants improved when both systems were trained together, compared to less than 30 percent when only the pelvic floor was targeted. Another study on women with pelvic organ prolapse found that core stability exercises were more effective than electrical therapy for improving pelvic floor strength.

But there is an important caveat. Not all core exercises are appropriate for people with hypermobility. Traditional movements like crunches, planks, or bracing techniques can put extra pressure on the pelvic floor. If someone already has an overactive or poorly coordinated pelvic floor, that pressure has to go somewhere. And often it goes down.

This can lead to symptoms like leakage, heaviness, pelvic pain, or constipation. That is why proper assessment is so important. We need to know whether the pelvic floor is too weak, too tight, or just not firing in the right way. Only then can we design exercises that actually help.

In hypermobility, the pelvic floor often needs less tension and more coordination. That’s why Kegels are not always the answer. Many people with hypermobility already have tension or imbalance in the pelvic floor. Telling them to squeeze harder just adds more fatigue to an already overwhelmed system.

What works better are slower, more controlled exercises. Things like pelvic tilts, shoulder bridges, or prone movements that help the core and pelvic floor activate together. These exercises teach the nervous system how to coordinate movement again. And that is the real key to building stability.

We also know that hypermobility is never just about one joint or one muscle. It is a systemic condition. Which is why full-body integration is so important. The goal isn’t just to have a strong core. The goal is to help the body move in a way that feels natural, supported, and safe.

So yes, core stability training can absolutely help with pelvic floor dysfunction in hypermobility. But only if the training is specific, well-paced, and based on what the person in front of you actually needs.

Could Core Exercises Be Harmful for the Pelvic Floor?

This is a question that comes up a lot, and honestly, it’s a good one. If you’ve ever leaked during a workout, felt pressure or heaviness after doing core exercises, or found that your pelvic symptoms got worse after certain movements, you’re not imagining it.

Core training can absolutely affect the pelvic floor. The issue isn’t that core exercises are dangerous, but that some are poorly matched for the needs of people with hypermobility or pelvic floor dysfunction.

Let’s start with what actually happens during a typical core exercise. When you brace your stomach or hold a plank, you increase the pressure inside your abdominal cavity. That’s called intra-abdominal pressure, and it has to be regulated by your core system, including your pelvic floor. In someone with a well-functioning pelvic floor, this system handles the load pretty efficiently. But in hypermobility, things are often a little different.

If the pelvic floor is too weak, too tight, or just not coordinating well with the rest of the system, that pressure builds with nowhere to go. This can lead to more leakage, more pressure, and sometimes even prolapse symptoms. And in a system already dealing with lax connective tissue, it’s easy to see how problems can start to creep in.

That doesn’t mean core work should be avoided. Far from it. But it does mean we need to be smarter about how it’s done.

The research tells us that people with EDS often experience a mix of pelvic floor dysfunction types. Some have muscles that are underactive and lengthened. Others have overactive and tense muscles. Many experience both at different times. This means that one-size-fits-all programmes, especially those that rely on repetitive bracing, planks, or crunches, can make things worse.

A lot of people are taught to squeeze, lift, and hold their pelvic floor without ever being shown how to relax it. For someone with a hypertonic pelvic floor, this just adds more tension and fatigue to an already overloaded system.

That’s why understanding what kind of pelvic floor you’re working with is so important. Before jumping into core exercises, we need to know whether that system can contract, relax, and respond to pressure in the way it’s supposed to.

If it can’t, forcing more reps, more effort, or more pressure will not fix the problem. It will likely amplify it.

This is why we always recommend starting with slow, controlled movements that help build awareness and coordination. Exercises that teach the core and pelvic floor to activate together, without excess pressure or bracing. These can look very different from what most people picture when they hear the words “core training.”

So can core exercises harm the pelvic floor?

Yes, they can, if they’re not the right ones, or if they’re done with poor technique or without the right foundation in place. But when done properly, they can also be one of the most helpful tools for improving pelvic floor function, not just in hypermobility, but across the board.

The key is in the approach, not the exercise itself.

So, are core exercises for hypemrobility/EDS a good idea?

There’s a lot of noise out there when it comes to core training. If you’ve been told your pain is because of a weak core, or that you need to brace harder to stop your joints from falling apart, it’s completely understandable that you’d feel confused or even frustrated.

But here’s the truth. The body is complex, and so is pain. A weak core isn’t the root of all problems, and a strong one isn’t a guarantee of stability or relief. Especially not in hypermobility.

What the evidence actually tells us is that core training can help. Not because it strengthens one muscle in isolation, but because it can improve coordination, body awareness, and support when it’s done well. And when it’s done in a way that respects how your body works, it can also support pelvic floor function, improve confidence in movement, and reduce symptoms.

But none of this works if the exercises are wrong for your body. Traditional core work that focuses on force, repetition, or bracing often misses the mark. Especially if your pelvic floor is already struggling or your joints feel unstable. What you need is an approach that meets your body where it is.

That might mean slowing down. It might mean starting with breathing and awareness before you even think about crunches or planks. It might mean stepping away from exercises that don’t feel right, even if everyone else swears by them.

And that’s okay.

You don’t need to be perfect. You don’t need to fix every joint at once. You just need a way forward that works for you, and a plan that respects the full picture of your body.

Core exercises can be part of that plan. But they should never be forced, feared, or followed blindly.

You’ve got other tools. You’ve got options. And most importantly, you’ve got time to figure out what works for you.

So, I if you want, you can try some different core exercises than you will be used to, below.

Enjoyed Our Blog? Why Stop Here?

If you’ve found value in our posts, imagine what you’ll gain from a structured, science-backed course designed just for you. Hypermobility 101 is your ultimate starting point for building strength, stability, and confidence in your body.

References:

Allison, G.T., 2012. Abdominal muscle feedforward activation in patients with chronic low back pain is largely unaffected by 8 weeks of core stability training. Journal of Physiotherapy, 58(3), p.200.

Coulombe, B.J., Games, K.E., Neil, E.R. and Eberman, L.E., 2017. Core stability exercise versus general exercise for chronic low back pain. Journal of Athletic Training, 52(1), pp.71-72.

Hodges, P.W. and Richardson, C.A., 1996. Inefficient muscular stabilization of the lumbar spine associated with low back pain: a motor control evaluation of transversus abdominis. Spine, 21(22), pp.2640-2650.

Lederman, E., 2010. The myth of core stability. Journal of Bodywork and Movement Therapies, 14(1), pp.84-98.

Lima, P.O., Oliveira, R.R., Moura Filho, A.G., Raposo, M.C., Costa, L.O. and Laurentino, G.E., 2012. Concurrent validity of the pressure biofeedback unit and surface electromyography in measuring transversus abdominis muscle activity in patients with chronic nonspecific low back pain. Brazilian Journal of Physical Therapy, 16(5), pp.389-395.

Luomajoki, H., Kool, J., De Bruin, E.D. and Airaksinen, O., 2007. Reliability of movement control tests in the lumbar spine. BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders, 8(1), p.90.

Luomajoki, H.A., Beltran, M.B., Careddu, S. and Bauer, C.M., 2018. Effectiveness of movement control exercise on patients with non-specific low back pain and movement control impairment: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Musculoskeletal Science and Practice, 36, pp.1-11.

Mannion, A.F., Caporaso, F., Pulkovski, N. and Sprott, H., 2012. Spine stabilisation exercises in the treatment of chronic low back pain: a good clinical outcome is not associated with improved abdominal muscle function. European Spine Journal, 21(7), pp.1301-1310.

Marshall, P.W., Desai, I. and Robbins, D.W., 2011. Core stability exercises in individuals with and without chronic nonspecific low back pain. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 25(12), pp.3404-3411.

Saragiotto, B.T., Maher, C.G., Yamato, T.P., Costa, L.O., Costa, L.C., Ostelo, R.W. and Macedo, L.G., 2016. Motor control exercise for nonspecific low back pain: a Cochrane review. Spine, 41(16), pp.1284-1295.

Smith, B.E., Littlewood, C. and May, S., 2014. An update of stabilisation exercises for low back pain: a systematic review with meta-analysis. BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders, 15(1), p.416.

Steiger, F., Wirth, B., de Bruin, E.D. and Mannion, A.F., 2012. Is a positive clinical outcome after exercise therapy for chronic non-specific low back pain contingent upon a corresponding improvement in the targeted aspect(s) of performance? A systematic review. European Spine Journal, 21(4), pp.575-598.

Stockard, A.R. and Allen, T.W., 2006. Competence levels in musculoskeletal medicine: comparison of osteopathic and allopathic medical graduates. The Journal of the American Osteopathic Association, 106(6), pp.350-355.

Vasseljen, O., Unsgaard-Tøndel, M., Westad, C. and Mork, P.J., 2012. Effect of core stability exercises on feed-forward activation of deep abdominal muscles in chronic low back pain: a randomized controlled trial. Spine, 37(13), pp.1101-1108.

Wang, X.Q., Zheng, J.J., Yu, Z.W., Bi, X., Lou, S.J., Liu, J., Cai, B., Hua, Y.H., Wu, M., Wei, M.L. and Shen, H.M., 2012. A meta-analysis of core stability exercise versus general exercise for chronic low back pain. PLoS One, 7(12), p.e52082.

Wong, A.Y., Parent, E.C., Funabashi, M. and Kawchuk, G.N., 2014. Do changes in transversus abdominis and lumbar multifidus during conservative treatment explain changes in clinical outcomes related to nonspecific low back pain? A systematic review. The Journal of Pain, 15(4), pp.377-e1.