- POTS and Exercise: The First Step Everyone Misses - 27 June 2025

- The Missing Link Between Breathlessness, Fatigue, and Chronic Pain: Understanding CO₂ Tolerance - 19 June 2025

- What is Mast Cell Activation Syndrome? - 12 May 2025

It seems like every week a question about running with hypermobility comes up with a new client of ours in the studio. As usual, there is always a lot to cover within this topic, as when it comes to hypermobility, there is an alarming amount of misinformation surrounding the topic.

There seems to be at the forefront two main camps of thought surrounding the topic of running with hypermobility:

The “you should definitely run if you are hypermobile” camp and the “you should definitely not run if you are hypermobile” camp.

Unfortunately, both camps tend not to be especially objective in their reasonings. You can find a great many hypermobile individuals who will attest that taking up running helped their hypermobility to no end, whilst in the same breath finding just as many who blame running for making their issues worse.

So, where do we start then?

Well, it’s not so much a complicated question, but more the fact that you need to know a few things before the question can be answered.

We work mainly with those with Ehlers-Danlos syndrome(EDS) and hypermobility spectrum disorder(HMSD), and many of our clients take up running as a hobby post rehab programme, all with 0 complications. However, hypermobility is complex, and EDS and HMSD are not the only causes of hypermobility.

So, as you can see, our answers need to cover a few bases before we give it.

As the cause of your hypermobility is going to be one of the largest contributors to deciding if you can or indeed should run, I always feel that understanding the different reasons that can lead to an individual becoming hypermobile in the first place, is always a good place to start, and often it is the most simplest place to start.

There are 3 main reasons why an individual will be hypermobile, and whilst people generally only tend to fit into one category, it is not uncommon for hypermobile individuals to move into more.

These reasons are:

- Medical-related reasons

- Structurally related reasons

- Injury-related reasons

This article covers:

ToggleMedical reasons

Certain medical conditions such as Downs syndrome, Ehlers-Danlos syndrome (EDS), Morquio syndrome, and Hypermobility spectrum disorder, are all medical conditions that result in connective tissue laxity in some form or another. And by this, I mean that each condition listed above can cause hypermobility through a different route. If we take Morquio syndrome, hypermobility is presented in a more limited distribution than say conditions such as EDS. Those with Morquio syndrome are unable to break down sugar chains (glycosaminoglycans) that help build bone, cartilage, eye corneas, skin and connective tissue (such as tendons, ligaments). This, in turn, leads to hypermobility being achieved in a more indirect fashion than that of conditions like EDS where laxity is caused by faulty collagen production.

Structural reasons

Certain structural conditions such as shallow sockets or hip dysplasia, wherein the hip socket doesn’t fully cover the ball portion of the upper thighbone can allow the hip joint to become partially or completely dislocated. In some studies, we find an 83.3% prevalence of hypermobility in those with dysplasia.

Injury reasons

Certain injuries such as anterior cruciate ligament(ACL) rupture can cause hypermobility in the knee joints of those who do not possess connective tissue disorders. In fact, whilst some of the research is conflicting, there is a lot of research to suggest hypermobility to be the main cause of ACL ruptures, especially as around 70% of ruptures are from non-contact events. The prevalence of generalised joint laxity in those who presented for an ACL reconstruction was 42.6% (72 of 169). However, the prevalence of generalised joint laxity in the control group was 21.5% (14 of 65). This difference is statistically significant

Who should run with hypermobility

After taking a quick look at the various reasons that cause hypermobility, it leaves us with the question “Who should run?” Those with structural issues are by far the hardest to answer this question for, as there are many variables at play and each type of structural issue will be slightly different to the last.

Running with structural issues

With issues such as hip dysplasia, they are normally first observed at birth, and treatments such as soft and hard braces can be used to help reshape the joint, as well as using various surgical interventions. For those with hip dysplasia who are older, such as teens and adults, as long as the dysplasia is mild, arthroscopic surgery can be very successful. However, for more serious cases, surgery such as a periacetabular osteotomy is much more likely to be needed, as this cohort being older, are more skeletally mature.

The general consensus of whether to run or not with hip dysplasia is surprisingly sparse. There are many people who have had 0 issues when returning to running after surgery, yet many have shown an increased rate of wear and tear of their prosthetic joints from high impact activities such as running.

For example, one study followed more than 600 people with hip replacements for an average of five years, but only 23 ran after the surgery. Although none of the runners had bad outcomes, the sample size was far too small to set running as a safe post-surgery exercise though and left many in limbo.

Whilst you may be able to run after hip dysplasia, is it a good idea?

Most likely not. However, you are the expert on your body, you know what feels good to do and what doesn’t, so a chat with your healthcare professionals about your individual situations is likely the best option, and running could very well be an option for you after some gently graded loading and a carefully crafted running programme.

Running after an injury

For those of you reading who are post-surgery, and those who are asking if they will be able to run again after ACL surgery, it’s a resounding yes.

However, returning to running safely is going to take some patience.

Around 16 weeks after ACL surgery is the general consensus to get back into activity, but this comes with a pretty large caveat.

In order to return to running, you need to follow certain post-op rules, such as easing back into regular leg movement (extension and flexion) around 4 days after surgery. This is especially important to stave off stiffening up and to help reduce post-op swelling, whilst also restoring full range of movement. Many people make the mistake of staying inactive after their op and this makes recovery difficult, let alone returning to running.

Running after Injury, especially hypermobility related injury, falls into the same rehab principles as it does for those with conditions such as Ehlers-Danlos, and we will cover these in the sections below.

Running with medical conditions

Downs syndrome: When it comes to hypermobile running with a medical condition, again it really depends on the person and indeed the medical condition. For those with D0wns syndrome, individuals generally exhibit low aerobic fitness scores as a result of a reduced red blood cell count, this can create a large barrier as Trisomy 21 (T21), the etiological factor of Down syndrome, has been shown to cause chronic autoinflammation, causing alterations in the life span and size of a red blood cell.

A reduced red blood cell count can easily result in what is known as chronotropic incompetence (CI), which is generally defined as the inability to increase the heart rate (HR) adequately during exercise to match cardiac output to metabolic demands. However, plenty of studies have been conducted into physical exercises and down syndrome, One such reported that over the course of 12 weeks, 52 adults with Down syndrome participated in a training program that consisted of 30 minutes of cardiovascular exercise and 15 minutes of strength exercise performed three days per week.

At the conclusion of the program, the individuals in the experimental group showed significant gains in cardiovascular fitness, muscular strength and endurance when compared to the control group, which had not participated in any exercise. It is possible that if this study lasted longer than 12 weeks, the gains may have been even greater.

Research also suggests exercise training can also improve oxidative stress in those with Downs syndrome. Although less well-understood, there is also a potential for improved motor learning in individuals with DS as a result of exercise participation.

As far as running is concerned, as long as a training plan is in place to grade activity in a safe way, help stabilise hypermobile joints, and keep the activity stimulating, those with Downs syndrome can indeed run and enjoy it as a sport or hobby. By far one of my favourite stories is that of Michael Beynon who was the first man with Downs syndrome to complete the London marathon.

Morquio syndrome: Conditions such as Morquio syndrome can make exercise such as running extremely complicated, and unfortunately, potentially unsafe. In many studies, musculoskeletal diagnoses were very common, with around 90% of subjects reporting abnormal gait, genu valgum, short stature, and/or short neck and joint contractures and subluxation in 52% and 47%, respectively.

Due to issues with gait and knocked knees, these biomechanical issues have the potential to make running painful and drastically increase the risks of subluxations and dislocations. Especially considering that in studies we find cervical spinal instability (49%) in almost half the population.

One of the most dangerous aspects of Morquio syndrome is that in studies it was observed that over half (51%) of the subjects had nervous system disorders, including 30% with cervical myelopathy, 14% with cervical cord compression, and 13% with thoracolumbar cord compression. Because of the issues discussed above, along with airway blockages and the fact that older patients tend to have more severe exercise and respiratory capacity limitations, and more frequent cardiac pathology, it means that running will most definitely place unwanted strain on an already strained system. Therefore when it comes to the topic of running and hypermobility, it is not advised to run for this population.

By now, hopefully, you are starting to see that the question ” Can I run with hypermobility?” is a lot more complex than it first seems. And as stated before, is largely due to the fact that hypermobility is acquired in various ways.

Hypermobile EDS

Conditions such as hypermobility spectrum disorder and Ehler-Danlos syndrome (hypermobility type) are who we get questions about running from the most, as this cohort is the one we work with every day.

Like injury-related hypermobility, connective tissue disorders such as EDS (hypermobility type) and hypermobility spectrum disorder (HMSD), are conditions that need to be worked with in a very specific way.

There is much content on the internet regarding stabilising hypermobile joints, however, there are a few common misconceptions and logical fallacies associated with these training routines, which we will cover in the following section. For those with hypermobility from EDS or HMSD, as long as a few key points are hit within their training, running is not only possible, but can also help to further stabilise joints, dissipate ground reaction forces more easily, and can become a very enjoyable form of exercise.

Running with hypermobility spectrum disorder and hypermobile EDS

After looking at the various reasons why people are hypermobile in the first place, and discussing who should and probably shouldn’t run, it leaves us with individuals who are rehabbing after ACL surgery and those with hypermobile EDS and HMSD. But, as individuals with hypermobile EDS and HMSD are the type of clients that we work the most with, both in-person and online, we are going to focus the rest of this blog on this type of client.

Please keep in mind that this area does not have a great deal of research. In fact, as of 2022, a search for Ehler-Danlos syndrome between 1935 – 2022 only yields 4,458 results. These results also tend to drop once you start to get more specific. The problem we face is that the research has gone in the total opposite direction of which we needed it to go. This has resulted in us having to conduct our own research with volunteers, which in turn, has actually been a major benefit for us, as we continue to explore our own theories and conduct our own research.

As you can see from the videos below, we have had great success in our methods at turning the most unstable of hypermobile joints, into strong and capable joints, easily able to handle the load from running.

When it comes to running hypermobility, there are 4 factors above all, that need to be addressed first, in order for those with hypermobility to ensure that running can be done both easily and safely.:

- Proprioception (Maps)

- Load

- Perturbation

- Absorption of force

Proprioception

Proprioception is what most reading will be used to hearing. However, proprioceptive training is a pretty redundant term, akin to be asking you to focus on your eyesight. Like proprioception, your eye site is determined by many internal and external factors, the health of the eye itself, weather conditions, lack of disease, etc. The same is true for proprioception. Proprioception is the effect, not the issue to be focusing on.

Traditional proprioception focuses on three aspects, known as the ‘ABC of proprioception’. These are agility, balance, and coordination. Agility is the capacity to control the direction of the body or body part during rapid movements, while the balance is the ability to maintain equilibrium by keeping the line of gravity of the body within the body’s base of support. Coordination is the smoothness of an activity. This is produced by a combination of muscles acting together with appropriate intensity and timing

A quick google result of proprioception will yield many exercises that claim to increase your proprioception, all focusing on these three aspects, however, as many will find, they simply don’t work very well. This is because of a few overlooked factors when it comes to proprioception: factors that result in the state of proprioception, one such factor is your maps.

If I were to ask you to meet me at a certain location in a national park, but provided you will a map lacking in detail and points of interest, then you would likely find it hard to get where you wanted to be. Likewise, if my daughter had smeared an abundance of chocolate over the map, it would make it difficult to read. The body is no different. The areas of your body you can feel and move are all mapped and represented within your brain. Areas of great importance such as hands have a much greater brain real estate, as we are incredibly tactile creatures. Whilst areas like your shins have much smaller areas dedicated to them as they are just not as important.

Without a clear map of your body, it does not matter how well your vestibular system works, how well your balance is, or how slow you perform a movement, the underlying cause of poor proprioception is not being addressed. With hypermobility, there are a great many factors that can blur your map, resulting in poor proprioception and unstable joints. One such factor is nociception.

Nociception is what we first referred to as “pain receptors” back in 1664. Unfortunately, we are still paying the price for this grave mistake. We now know that pain is not an input to the body, but rather an output of the brain, and nociception is not mutually exclusive with this process. Nociception is for all intents and purposes, the mechanism by which noxious stimulus is reported. Anything our brain may deem as an extreme, such as temperature, chemicals, vibrations, and pertinent to hypermobility, stretch.

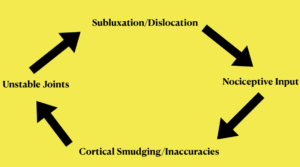

When you sublux or dislocate a joint, ligaments are overstretched and nociception occurs to inform the brain of noxious stimulus at the dislocation site. Depending on the level of subluxation/dislocation, nerves and blood vessels may be damaged, muscles and ligaments may tear, the joint will swell, compression of nerves may cause tingling, and an inflammatory response will be activated.

Nociceptive signals to the brain can easily impair cortical maps as nociceptive signals are prioritised to reach their body part representation in the brain over other receptor types, as nociceptors detect potentially dangerous stimuli and are therefore more important. However, this process can be reversed as you will likely have found out after stumbling your toe and having the innate urge to rub your foot, sending non-nociceptive signals to drown out the nociceptive ones. Any further movement to a dislocated joint will also fire off further nociceptive signals, especially when they try to relocate their dislocated joint.

If the joint subluxes and the joint is displaced partially, but then immediately returns to a normal position, then they will likely avoid damage to the joint, and instead suffer from swelling and inflammation immediately after the sublux.

The issue you, as a hopeful hypermobile runner faces, is that nociceptive inputs create inaccuracies in the cortical map which impairs the brain’s ability to stabilize joints. In the days after a sublux/dislocation, it is normal for a protective response to occur byways of the nociceptive threshold lowering, and you may find that pressure or movement that wasn’t especially painful before, now is. This drop-in threshold results in pressure, movement, stretch, and chemicals that would normally be perceived as non-nociceptive, to now be perceived as nociceptive, and to contribute to further inaccuracies being created in your cortical map.

The more inaccuracies/smudging in your cortical map, the less the brain is able to locate and stabilize the joint, which results in a greater chance of further subluxation/dislocation. Here at The Fibro Guy, we called this the sublux/dislocation cycle. We also need to take note that moving the body part less incurs more inaccuracies, as this limits proprioceptive signals. Then there’s other issues with low Co2 levels that alter the brains mapping system.

It is not uncommon for those with hypermobility to dislocate joints fully, multiple times a day, and will likely, in a bid to stop dislocation, Immobilise the joint byways of a sling for shoulders, etc. However, immobilization can lead to hypoxic and inflammatory conditions in the joint capsule, which can easily become an initiating factor for issues such as joint contracture, as well as sending constant nociceptive signals causing even more cortical inaccuracies.

Load

To be able to run with hypermobility, we need stable joints, and most with hypermobility will have been told at some point or another, either by their GP, or multiple physiotherapists, that the solution to stopping joint dislocations is to build muscle around the joint. This poses two main issues, the first, being that growing muscle tissue comes with certain prerequisites to actually achieve muscle growth, mainly that tissue needs to be sufficiently loaded to initiate growth.

However, to be able to put such load through a tissue to force growth, a joint needs to be stable enough to manage the load. If a joint is unstable, sufficient load can not be put through a joint to actually increase muscle tissue.

The second issue with current treatments is that the average male, with all their testosterone, can only realistically add about 8-12lb(depends on who you ask) to their frame, distributed bodywide, and for women with significantly lower testosterone, they will add significantly less muscle tissue.

So, are you expected to wait 5 years for enough muscle tissue to be added to stabilize a joint? In fact, how long would it take and how much muscle is needed?

Also, how do our hypermobile clients go from multiple dislocating joints, only for 5 weeks later to have their joints stable, when they have gained 0 muscle tissue?

Obviously, the answer is that the amount of muscle tissue is irrelevant in stabilising the joint, it is only the brain’s ability to locate and stabilize their joint that is important. Far too much emphasis has been placed on the musculoskeletal factors for rehab when they should have been placed neurologically.

Once the sublux/dislocation cycle has been broken, and nociceptive information is no longer smudging maps, load needs to be put through the joint, not only to help reinforce the maps but to get the tissue used to handle load in general. A go-to exercise for those with hypermobility looking to get into running is clams and bridges. However, these exercises are not translatable to everyday movement, for reasons I explain in the video below. These exercises do not put a sufficient load through the joint to receive any kind of meaningful or translatable benefit.

Load that is transferable and safe, will not only help update your cortical maps, but will create stronger, healthier, and more reactive tissue. After all, this is half the battle, as it doesn’t matter how strong your muscles are, it’s about whether the brain can locate and contract them, and most importantly how fast it can do this.

Perturbation training

Perturbation refers to the deviation of a system from its normal path due to outside influence. When running with hypermobility, this is something you will need to be able to handle as you traverse different terrain. As most hypermobile accidents are caused by an outside influence, such as stepping off an uneven curb or being knocked in the street) it makes sense for you to train to be able to quickly react to external influences to avoid injury. As we discussed above, it is not how strong your tissues are that matters, but rather your brain speed at locking and stabilising your joints.

This type of training involves delivering random and continual force whilst moving through simulated movements you will perform when running. This stresses the nervous system to react quickly to forces that you cannot predict. But, more importantly, it creates a neural network for stability against actions that would likely cause dislocations, that can be activate automatically.

Shock absorption

When your maps have been updated, you can place load through the joints, and even deal with perturbation, then you are ready to learn how to absorb the shock from running. In the studio we find that around 6 weeks of mapping and loading are sufficient to move on to shock-absorbing, providing our clients have been sublux/dislocation free for 5 weeks.

Keep in mind, that when you run, you are putting your body weight into the ground, and every action has an equal and opposite reaction, which mean that the ground is going to push back at you. Because of this, you need to be able to dissipate that force through your joints and tissue. Because if you don’t, your joints are going to take the brunt of the force, and running is not going to be enjoyable. It’s also likely to cause nociceptive pain and smudge out your maps causing even more issues.

The mistake most make with learning to absorb shock, is that they haven’t focused on the three earlier points, which means they have little control over their joints, and their muscle can not contract fast enough to absorb force or use the tissue properly, leading to at best, pain, and at worst, a dislocated joint.

When your feet hit the ground your joints need to collapse in a controlled fashion to absorb the force, whilst stabilising and contracting to generate force to propel you foward. This means that you need to be able to achieve good flexion mechanics to properly absorb and create force when running with hypermobility. Good flexion mechanics are around: 30 degrees for hips, 40 degrees for knees, and 20 degrees for ankles. These angles will provide you with the greatest stability through muscle contraction and less impact-related injuries.

But, before you get into running, it is a good idea to trial gentle shock-absorbing exercises, such as slow controlled jumping actions. Whilst paying attention to absorbing the force. If you are silent whilst jumping it shows you are on the right track, if not, more practice is needed. Rather than landing with a thud and feeling the shock wave travel up your body, you should feel your ankles, knees, and hips all collapse as soon as your feet hit the floor.

Likewise, something else to consider is that most of the time spent running is on one leg, which means not only do you need to absorb force, but you are also going to be doing so unilaterally.

Do’s and don’t of running with hypermobility

Below are some points we believe you should definitely pay attention to when it comes to running with hypermobility:

- Bend your knees: You should avoid heel striking with a straight leg, as this will cause the impact to be amplified throughout your body due to a longer stride. Try and focus on bending the knee at impact or switching to forefoot running.

- Focus on your TA: We notice a lot of the hypermobility population have issues with the Tibialis Anterior. The Ta is responsible for lifting your foot when running, whilst also stabilising your ankle.

- Focus on your maps: Keeping your cortical maps updated will ensure your joints stay stable whilst running.

- Don’t stretch beforehand: As we discussed in the stretching blog found here, running doesn’t do half of what we thought it did. Stretching before a run can lead to less force production and actually increase our risk of injury. Instead, warm up your nervous system with a slow walk that moves to a brisk walk, and then start your run.

I could have written another 4000 words easily on this topic, as it’s one that I have always found fascinating. Likewise, we have only really just scratched the surface of this topic, so if there is interest, I am more than happy to record some videos and write some more content on some of the techniques we have mentioned above, and do a part 2 to the topic.

From all of us here at The Fibro Guy, good luck with your running!

Enjoyed Our Blog? Why Stop Here?

References:

Aman, J.E., Elangovan, N., Yeh, I-L. and Konczak, J. (2022) ‘The Effectiveness of Proprioceptive Training for Improving Motor Function: A Systematic Review’, Frontiers in Rehabilitation Sciences, 3:830166.

Aydin, B.K., Yilmaz, C., Yildiz, V., et al. (2022) ‘Does anterolateral ligament internal bracing improve the outcomes of ACL reconstruction in patients with generalized joint hypermobility? A retrospective study’, Orthopaedic Surgery, 14(3), pp. 503–510.

Bennett, A.N., et al. (2025) ‘Hypermobility Spectrum Disorders and Pain: A Review of Recent Developments and Their Application to Clinical Practice’, Touch Immunology, 1(1), pp. 1–7.

BMJ Open Sport & Exercise Medicine (2018) ‘Hypermobility and sports injury’, 4(1):e000366.

Charbonnier, C., et al. (2021) ‘Hypermobile Disorders and Their Effects on the Hip Joint’, Frontiers in Surgery, 8:596971.

Jacobsen, J.S., et al. (2013) ‘Changes in walking and running in patients with hip dysplasia’, Acta Orthopaedica, 84(5), pp. 502–508.

Liaghat, B., Skou, S.T., Søndergaard, J., Boyle, E., Søgaard, K. and Juul-Kristensen, B. (2022) ‘Short-term effectiveness of high-load compared with low-load strengthening exercise on self-reported function in patients with hypermobile shoulders: a randomised controlled trial’, BMJ Open Sport & Exercise Medicine, 8(2):e001300.

Morrison, N., et al. (2021) ‘The GoodHope Exercise and Rehabilitation (GEAR) Program for People with Ehlers-Danlos Syndromes and Generalized Hypermobility Spectrum Disorders’, Frontiers in Rehabilitation Sciences, 2:769792.

Palmer, S., Bailey, S., Barker, L., et al. (2022) ‘Exercise and Rehabilitation in People With Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome: A Systematic Review’, Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 103(4), pp. 767–777.

Shadmehr, A., Jannati, E., Ghasemi, G.A., and Bagheri, H. (2018) ‘The effect of combined exercise therapy on knee proprioception, pain and quality of life in patients with hypermobility syndrome’, Physiotherapy Theory and Practice, 34(6), pp. 430–436.

Smith, T.O., Jerman, E., Easton, V., Bacon, H., Armon, K., Poland, F. and Macgregor, A.J. (2013) ‘The effectiveness of therapeutic exercise for joint hypermobility syndrome: a systematic review’, Physiotherapy, 99(1), pp. 1–8.